Whether you work as a healthcare provider, a therapist or counselor, or in law enforcement, you are in a position to impact the lives of people struggling with a substance use disorder (SUD) and their families. Substance use disorder can happen to anyone, and anyone can get help.

Substance use disorder, also known as addiction, is a treatable medical disorder. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines a moderate to severe substance use disorder as someone’s frequent and/or continued use of drugs or alcohol over a period of time, despite serious and negative consequences.

In 2021, over 80,000 people in Colorado said they needed substance use treatment but did not get it: 77% of those people said they didn’t seek treatment because of stigma (feeling shame and judgment).

How We Treat People Matters.

When people with SUDs are made to feel stigma or shame for their substance use—especially from people who are in a position to help them like doctors and nurses, therapists, or law enforcement—they are less likely to seek help or treatment in the future.

One study showed that healthcare providers who held stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors resulted in patients with an opioid use disorder (OUD) delaying seeking treatment by five to six years. Receiving discriminatory care and internalizing stigma delay treatment and perpetuate an individual’s ongoing use for years. People who delay treatment are at risk for additional harm due to their substance use, including overdose and death.

Dr. Nora Volkow, the Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the National Institutes of Health, states, “Stigma on the part of healthcare providers who tacitly see a patient’s drug or alcohol problem as their own fault leads to substandard care or even to rejecting individuals seeking treatment. People with addiction internalize this stigma, feeling shame and refusing to seek treatment as a result.”

Additionally, Dr. Sarah Wakeman, Medical Director for the Massachusetts General Hospital Substance Use Disorder Initiative and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, has argued that stigma in the medical community and the criminal justice system as the biggest barrier to fighting the opioid epidemic, underscoring the incredible importance of removing it in interactions with individuals with an SUD.

Seeking treatment for a substance use disorder is a major decision. People who work in the medical, behavioral health, and criminal justice fields can be an incredible support to someone who is ready to start their recovery, as well as people in active use—recurrence of use, also known as relapse, happens and is normal, but it’s essential that individuals know they can ask for help and they’ll receive it. It’s important to promote positive interactions and reduce stigma with every person you encounter—not just those who are ready for treatment.

Power of Language

Key Steps to Help Someone with a Substance Use Disorder

Use person-first language.

Person-first language emphasizes the individuality and dignity of someone, putting the person before their diagnosis, and showing respect for them as an individual. It’s important to be intentional about our words when talking about substance use disorder and recovery—even common terms can reinforce stigma. To learn more about person-first language and the terms you should be using, visit our person-first language page.

Be an ally.

Provide support to individuals with SUD and connect their loved ones to support. When discussing treatment options with someone, it’s important to meet them where they are at and share that you support all pathways to recovery.

Ask

Ask patients about substance use when in a healthcare setting, including when providing care in a jail. You are already treating them—this provides the opportunity for someone to feel comfortable asking for help, and you can provide more holistic and effective care.

Substance use disorders are treatable and recovery is always possible.

Your support and compassion can make a huge difference in someone’s substance use journey, no matter where they are in readiness for change. Within the healthcare field, in particular, patient-centered care empowers patients with information that helps them make better treatment decisions and reduce preventable harm from active substance use.

Educate yourself

Educate yourself on SUD and treatment options in your community so you can connect with someone to help. You can find more treatment options here and information on financial options for treatment here.

Additional Resources:

Those in health care can fight against stigma through the Reducing Stigma Education Tools (ReSET) program here. Learn how to implement evidence-based strategies.

The Basics of Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder

FDA-approved prescription medications such as buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone are used to treat opioid use disorders (OUD). These medications are safe to use for months, years, or even a lifetime, depending on the needs of each individual, and it has been proven that the longer they are taken, the less likely an individual is to overdose.

The science demonstrating the effectiveness of medication for OUD is strong. For example, methadone, extended-release injectable naltrexone (XR-NTX), and buprenorphine were each found to be more effective in reducing illicit opioid use than no medication in randomized clinical trials.

However, only about 19 percent of adults with opioid use disorder received medication for treatment in 2019, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

- Buprenorphine and methadone relieve opioid withdrawal, suppress cravings and block the euphoric effects of opioids.

- Naltrexone doesn’t relieve physical withdrawal, but it suppresses cravings, blocks the euphoric effects of opioids and can also be used to treat alcohol use disorder.

Methadone can be accessed via Opioid Treatment Programs, while buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed by licensed practitioners. Medications to treat opioid use disorder are effective and should be widely available, including through primary care, emergency departments, behavioral health facilities, and in jails.

Learn more about medications to treat opioid use disorder and the other strategies and services needed to support recovery in SAMHSA’s Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) 63 publication.

Medications for Treating Opioid Use Disorder

Prescribing Buprenorphine

Why It Matters

These numbers demonstrate just how challenging finding treatment can be and the need for more clinicians to familiarize themselves with buprenorphine prescribing and to become active prescribers. Waivers are no longer required to prescribe buprenorphine. Treatment should be available to anyone interested. Removing stigma and barriers to treatment, and increasing the number of clinicians educated on prescribing buprenorphine is essential to helping people.

What You Can Do

All professionals in the field can direct people to LiftTheLabel.org/GetHelp to find treatment resources in their area. If you’re a medical professional, you can learn how to start a hospital-based MOUD program and how to provide MOUD in the acute care setting.

Fentanyl & Naloxone

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin. Although fentanyl is an FDA-approved pain medication, the current opioid overdose crisis is being driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Fentanyl potency is extremely unpredictable—its effects are felt quickly and do not last very long (about 30–60 minutes).

As a result, people with an OUD may use it multiple times a day to stave off withdrawal symptoms. While some people use fentanyl intentionally, many individuals consume it unknowingly or unintentionally because it is present in other non-opioid substances such as methamphetamine, cocaine, etc. It is important to note that fentanyl cannot be absorbed by touch, so you cannot overdose from simply touching fentanyl.

Fentanyl test strips can identify the presence of fentanyl in unregulated substances. Being aware that fentanyl is present allows individuals to take the steps to reduce the risk of an overdose. Learn more about life-saving fentanyl test strips and find out if there are fentanyl test strips available near you.

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist used for the emergency reversal of opioid overdose, and is an essential tool in combating opioid and fentanyl overdose deaths. Learn more about where to get naloxone. NARCAN® naloxone nasal spray can now be found over-the-counter in stores.

The duty of first responders is preservation of human life, regardless of the person’s condition. Every person deserves a chance for recovery, and reversing a person’s overdose can provide them that opportunity. By Colorado law, anyone can obtain and administer naloxone to help someone who may be experiencing an opioid-related overdose. Good Samaritan and third-party laws protect health care providers and law enforcement from liability should they need to administer naloxone.

Law Enforcement & The Importance of Naloxone

Law enforcement agencies can greatly benefit from requiring officers to carry naloxone and training them to administer it. Officers are often the first on the scene and are uniquely positioned to save someone’s life. Officers have also reported that the requirement to carry and administer naloxone improves the public perception of law enforcement within a community.

If you administer naloxone, you have an opportunity to connect an individual and/or their friends and family with resources for treatment.

Medical Professionals: Prescribing Naloxone

Medical professionals should prescribe and/or recommend a nasal spray form of naloxone to:

- Patients who are prescribed opioids for pain

- People with active OUD

- Patients receiving medications for OUD

- People who have been discharged from emergency medical care following opioid poisoning or intoxication

- People being released from incarceration

- Friends and family of individuals at risk for an opioid overdose

Law Enforcement: Incarceration & Overdose

The risk of overdose death is drastically higher for individuals with an opioid use disorder (OUD) upon release from incarceration, particularly if an individual uses the same amount of opioids they used pre-incarceration, due to a significantly lower tolerance. According to a SAMHSA report, in jails and prisons that do not offer medications to treat OUD, relapse rates exceed 75% after release from custody.

As of July 1, 2023, Colorado has a statutory requirement that requires jails to screen inmates and offer medications for treatment such as methadone or buprenorphine.

Overdose death rates are 10 to 40 times higher for previously incarcerated people than for the general population, making drug overdose the leading cause of death for individuals re-entering society after incarceration. This highlights the incredible need for post-release support and treatment.

There’s a simple yet extremely effective way you can help: connect people to treatment facilities that offer medications to treat opioid use disorder and distribute naloxone upon release to reduce overdose deaths. Additionally, screening each person entering into custody for a SUD and taking medications to treat OUD (buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone) available while incarcerated has shown promising results for getting and keeping people in treatment and recovery, reducing recidivism.

What You Can Do

Criminal justice professionals can act as advocates for policy change. They can also educate themselves on treatment programs and options to recommend when interacting with people struggling with an SUD. Adopting a non-judgmental tone and approach when interacting with people with an SUD goes a long way. Law enforcement professionals can carry naloxone and encourage fellow officers to do so, and become educated on local treatment resources.

Further Reading on Incarceration and MOUD

Read more about jail-based medications for opioid use disorder in the National Sheriff’s Association and National Commission on Correctional Health Care’s guide and the Jail Based Behavioral Health Services (JBBS) Program in Colorado.

Behavioral Health Professionals: Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) and Counseling

Medication to treat OUD should be integrated with outpatient and residential treatment. Some patients may benefit from different levels of care at different points in their lives, such as outpatient counseling, intensive outpatient treatment, inpatient treatment, or long-term therapeutic communities. Patients treated in these settings should have access to medications to treat OUD.

Under federal law 42.CFR 8.12, patients receiving treatment in Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) must receive counseling, which may include different forms of behavioral therapy. These services are required along with medical, vocational, educational, and other assessment and treatment services. Regardless of how medications are provided, it is more effective when counseling and other behavioral health therapies are included to provide patients with a whole-person approach.

From the Experts

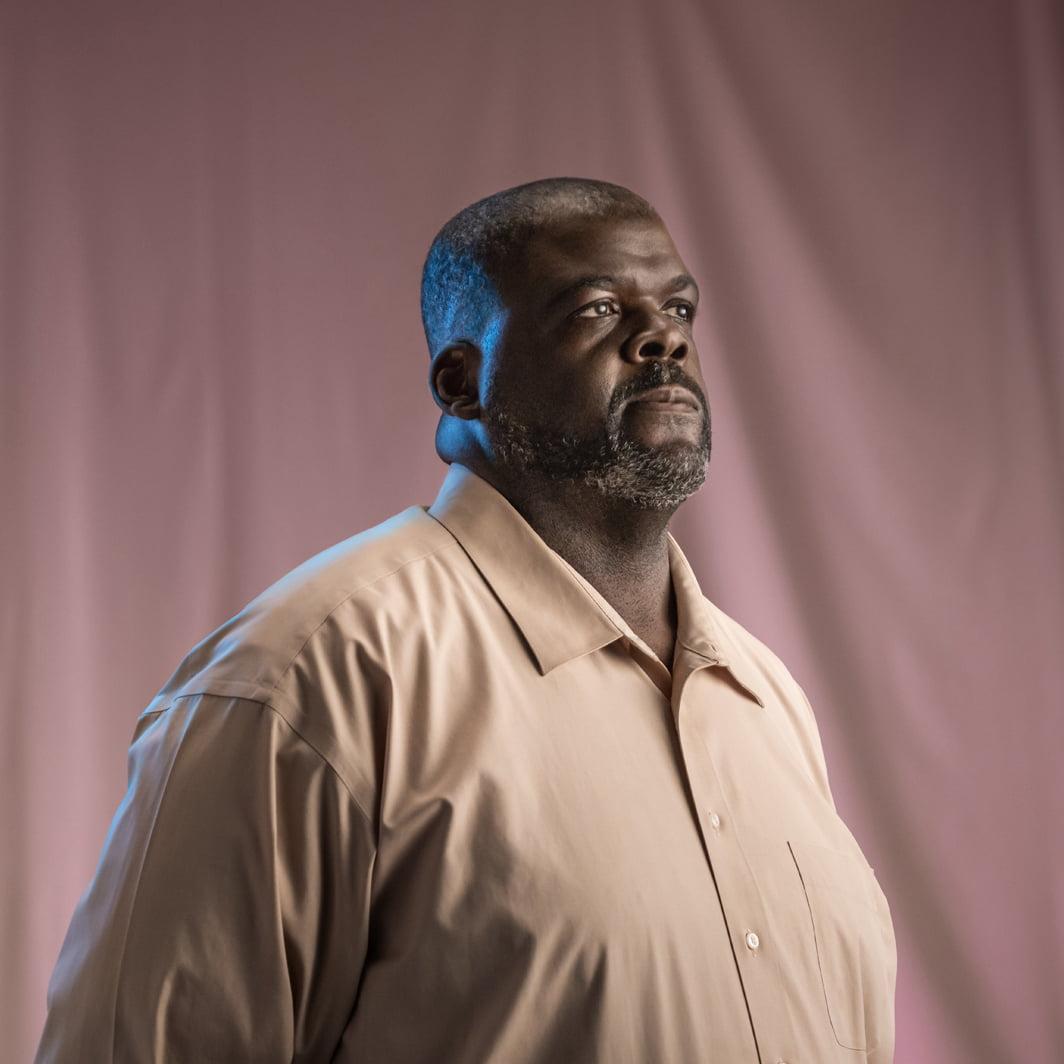

DONNA | Behavioral Health Services Director

More lives have been saved with this medication than any other type of treatment for opioid use disorder.

I knew I wanted to get into the world of treatment and counseling after witnessing the courage that recovery took, especially with the obstacles like cost and lack of support. It’s why I trained as a therapist and an addiction counselor. This field offers this really rewarding intersection of medical and behavioral health. As the director of Behavioral Health Services for a treatment center, I’m able to interact directly with patients while also managing grants that will have a profound impact on substance use disorder across the state.

There is no single way to help people struggling with a substance use disorder. We are all individuals and we need to be treated this way when it comes to medical issues. We offer our patients options like harm reduction and support programs, as well as medications.

Sadly, stigma exists even within the mental health field. I’ve heard therapists say, “I don’t treat people with addictions because they lie.” First of all, many people who don’t have a substance use disorder lie in therapy. Second, not everyone who struggles with a substance use disorder is going to lie. But most importantly, when you refuse to treat people with substance use disorder, you leave them without essential support. I believe substance use and mental health issues should be treated similarly, especially because they often go hand-in-hand.

Luckily, for behavioral health professionals, the medications for treating addiction are incredibly effective. There is a lot of clinical evidence demonstrating these medications’ effectiveness, especially when paired with other types of support. I tell other professionals that it’s not a cure-all or a miracle drug and that it won’t work for everyone, but when you look at the overall population, more lives have been saved with this medication than any other type of treatment for opioid use disorder.

The fentanyl crisis is staggering. We see it showing up in urinalysis during patient intake, even if they’re not using opioids. It’s essential that we educate people who are using substances, even recreationally. Fentanyl test strips offer one way for people to be informed so they can use safely, an important part of a harm reduction approach.

There’s an unfounded fear that harm reduction or destigmatizing substance use disorder will normalize it. That misconception leads to the idea that we must come down hard on people rather than be empathetic. But this mindset has not proved effective or productive. Instead, we need to acknowledge our fears. When we are responsible for that, we can approach the evidence and data to find the right solutions.

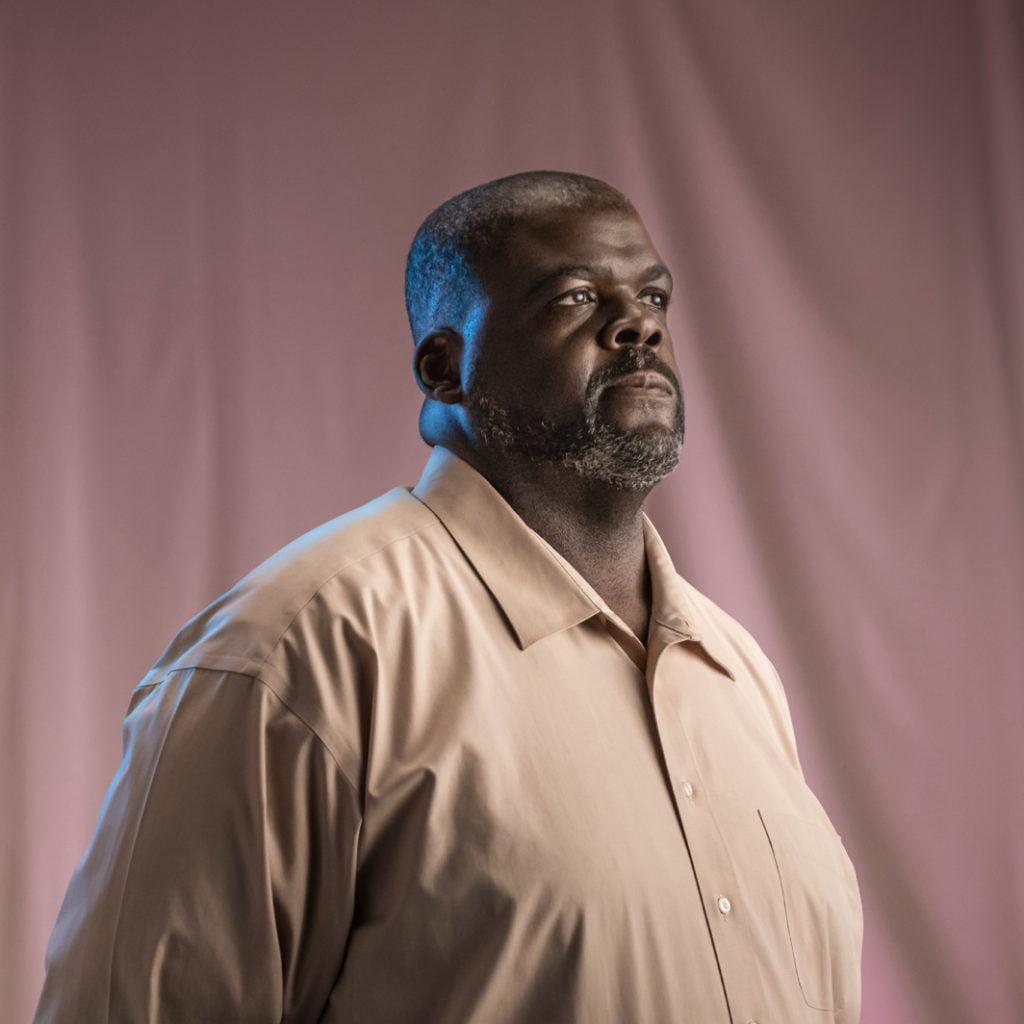

DR. LESLEY BROOKS | Greeley, CO

I want to break down these systemic barriers, creating easily accessible treatment services that make everyone feel seen and heard.

I’m a family medicine and an addiction medicine physician, and these two perspectives give me a unique view into the world of addiction treatment.

I come from a full-scope family medicine background, including everything from labor and delivery to pain to substance use. While every part of medicine is equally important, I saw addiction’s impact on Black, Brown, poor, and marginalized people and families. I thought I could make the biggest impact at the intersection of substance use, mental health, and marginalized communities. There are serious issues with how addiction and treatment are viewed in society and by the medical community. First, addiction is often treated as a lack of willpower, when in fact, it’s a chronic condition much like diabetes. Second, the same structural and systemic inequalities that exist in every other part of society are amplified in addiction and mental health treatment. Treatment can feel non-inclusive for communities experiencing vulnerabilities. People from the Black, Latinx and LGBTQIA+ communities face judgment and rejection or find treatment approaches that seem to be made for anyone but them. That’s something I’m advocating to change. I want to break down these systemic barriers, creating easily accessible treatment services that make everyone feel seen and heard. Without question, this is the work that gets me out of bed in the morning, that drives me to spend my days educating, advocating, and building towards change.

ANTOINETTE | Behavioral Health Program Director

One of the most encouraging things for someone struggling with addiction to hear is there are people who care about their recovery and who want to help.

I wanted to work in treatment after realizing there was a huge need. A lot of people are struggling with addiction, and not enough people are trained in treatment. It’s exciting to see people who want to make a change, especially with the help of medications.

Medications to treat opioid use disorder are exceptionally effective. These medications take care of the body and mind by combating cravings and reducing painful withdrawals. Treatment programs try to find the right medications for you based on your needs, and you are not locked into medication once you choose. Most programs offer other support like counseling, case management, and help finding a job. You will have a support system to help you set and achieve goals. Most treatment can be done through outpatient care, going to a treatment center to get medications regularly, and allowing you to go about your life. The goal with any treatment program you choose is to regain the life you envisioned for yourself.

There’s a misconception that using these medications trade one drug for another. No one should feel shame for needing medication. If you know someone who judges the use of these medications, people in the treatment community can help them understand it.

The cost of treatment may feel overwhelming, but there are more resources available than ever before. Medicaid and Medicare are the most widespread options and may cover 100% of your cost. Applying is easy, and treatment centers will help you with your application. Other payment options could include working with your insurance or providing a sliding scale fee or grant funding to find the most affordable payment option. No one is turned away from treatment because of cost.

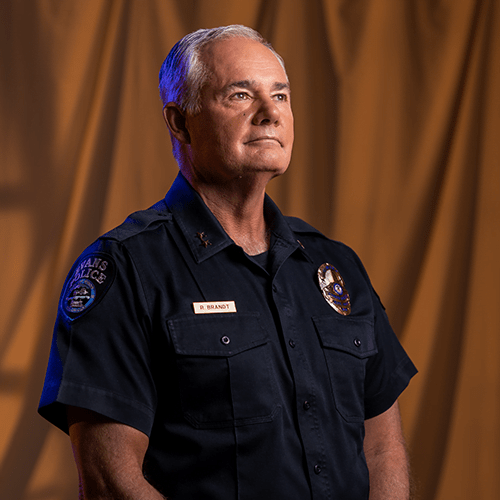

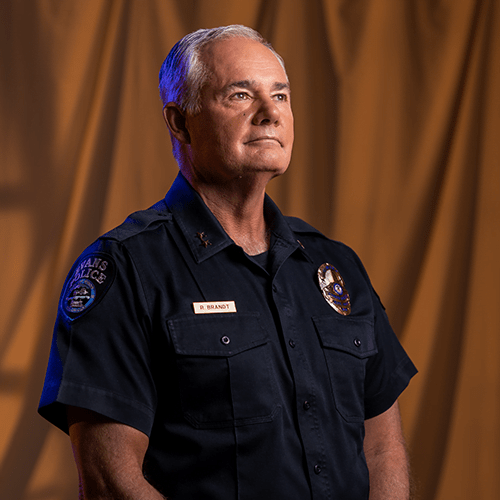

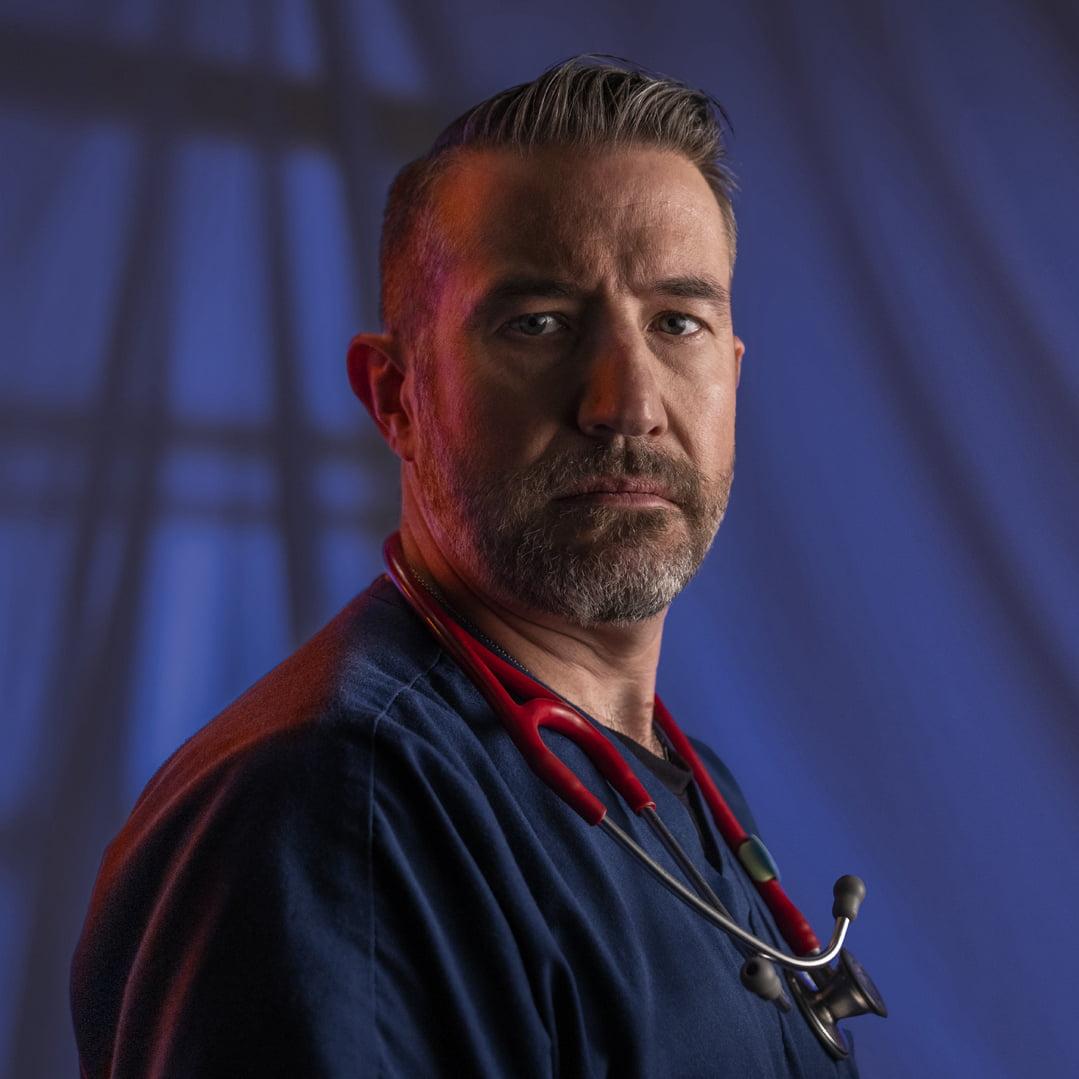

CHIEF RICK BRANDT | Evans, CO

I remind them that they took an oath to protect life. Naloxone does just that.

I’m Chief Rick Brandt. I’ve worked in law enforcement for over 40 years. Currently, I’m serving as the Chief of Police in Evans, CO.

I always knew I wanted to help people, and I thought the best way to do that would be as a police officer. My journey in law enforcement started in Aurora, CO, where I started as a regular officer and eventually worked my way up through the ranks.

Over the years, my attitudes toward addiction, incarceration, and rehabilitation have changed. My father struggled with addiction, and I couldn’t understand why he didn’t give it up. But a few things happened to me along the way. First, I was given a prescription for opioids after surgery and after just a few days, I could feel cravings. That was really eye-opening and helped me understand how addiction can begin for some people. More importantly though, I saw how locking people up for their addictions wasn’t helping them on the individual level and wasn’t having an impact on the larger community or the addiction crisis.

So, I dedicated my career and my energy toward shifting attitudes within police departments, encouraging policy change, and educating people on how to combat the opioid crisis. I’m a big proponent of a co-responder program. Rather than sending an officer alone, we advocate for sending someone who works in mental health or the recovery field along with the officer to respond to calls where a mental health resource might be needed. These professionals can offer resources and treatment options that can lead to real change rather than incarceration. I’m also a big supporter of offering programs to provide treatment using medications for opioid use disorder in jails, giving people the opportunity to access treatment so they can start fresh when they are released. Lastly, I’m an advocate for supplying first responders, especially police officers, with naloxone. Naloxone is a life-saving opioid overdose reversal medication. Law enforcement professionals often arrive first on the scene of an overdose. Putting this medication in officers’ hands can save someone’s life. Some people in the policing community resist this. They have a mindset of, “why am I saving someone who makes such risky decisions over and over?” To those folks, I remind them that they took an oath to protect life. Naloxone does just that. You can save their life and give someone a chance to find recovery.

MARVINA | Peer Recovery Coach

I got started as a peer recovery coach because I had the mindset that I wanted to be able to help just one person.

My first experiences with drugs and alcohol were at a very young age and were often encouraged by family members. Experimenting with drugs eventually became a habit, including stealing cocaine from my mom and missing school. After graduating high school, I started using meth and got arrested. I had an abusive partner, but I never left because I didn’t want to leave my children. I started selling meth and was even involved with a cartel—I knew I needed more from life, but I didn’t know what. After being arrested for selling meth, I went to inpatient treatment, and this was when things turned around for me. Through treatment and self-reflection, I was able to find recovery and keep my children.

Today, I am a peer recovery coach, offering emotional support, motivation, and encouragement to others who are still struggling with addiction. When you go through treatment, so many people tell you what you need to do, and you can’t help but think, “How would you know?” That’s why my lived experiences are so meaningful; I can relate to what others are going through because I know it.

When it comes to those conversations, it’s essential to give people the time and space to be ready and make sure they know everything is confidential and that you won’t judge them. You have to stay positive in your tone and your mindset. You can’t bring a damaged attitude to the peer recovery coach job. You have to try your best to be physically, mentally, and emotionally present.

It’s important to check in on people who we know need the most help managing their mental health and/or substance use diagnosis, and are at highest risk. We have to think about what they need and what they are going through. I try to focus on those one-on-one conversations, and I always leave on a positive note no matter what is going on in someone’s life.

Peer recovery coaches need to be good role models because everything you do in the community is watched. Your successes represent hope for others.

Honesty is the foundation of change. If you’re being honest with yourself, being honest with others comes easier. I got started as a peer recovery coach because I had the mindset that I wanted to be able to help just one person. Today, I know I’ve helped a lot more than that, and I will continue to do so.

DR. KAYLIN KLIE | Denver, CO

When you decide to open your arms to someone struggling with a substance use disorder, you’ve already made the most critical step, even if they’re not ready to seek treatment.

During my residency as a doctor, I loved spending time with expecting mothers, and at the same time, I became increasingly concerned about the opioid epidemic. This had me ask, “How did we get here?” and led me to my specialty of caring for pregnant women and mothers struggling with substance use disorder, who are in a really tough position. First, they need both prenatal care and treatment for a substance use disorder. Second, these individuals face a lot of stigma from society for experiencing a substance use disorder and pregnancy simultaneously.

There are a lot of misconceptions about pregnancy and substance use disorder. The first is “if a pregnant person loved the child, they would stop using” – but the ability to stop and care are completely different. Another misconception is “people who use substances can’t parent safely” – it’s possible for parents who use substances to parent responsibly and lovingly. Lastly, people assume someone who is pregnant needs to detox right away. In actuality, this can be very dangerous. Instead, we need to provide harm-reducing options that keep both mother and child safe.

Expecting mothers ask, “Is my baby going to be taken from me?” or “Did I hurt my baby?” These questions demonstrate mothers’ love, care and desire to parent. For me, these questions reinforce the fact that a substance use disorder does not make you a bad parent.

I’m in a fortunate position where I can offer mothers hope in a few ways. First, it’s not a guarantee that a substance use disorder will have long-term effects on a child. I can also offer treatment programs, resources and encouragement to people at a really important cross-road in their lives. And in return, they give me hope through their success stories and by witnessing their act as loving parents.

When you decide to open your arms to someone struggling with a substance use disorder, you’ve already made the most critical step, even if they’re not ready to seek treatment. You’ve left the door open to future dialogue and treatment.

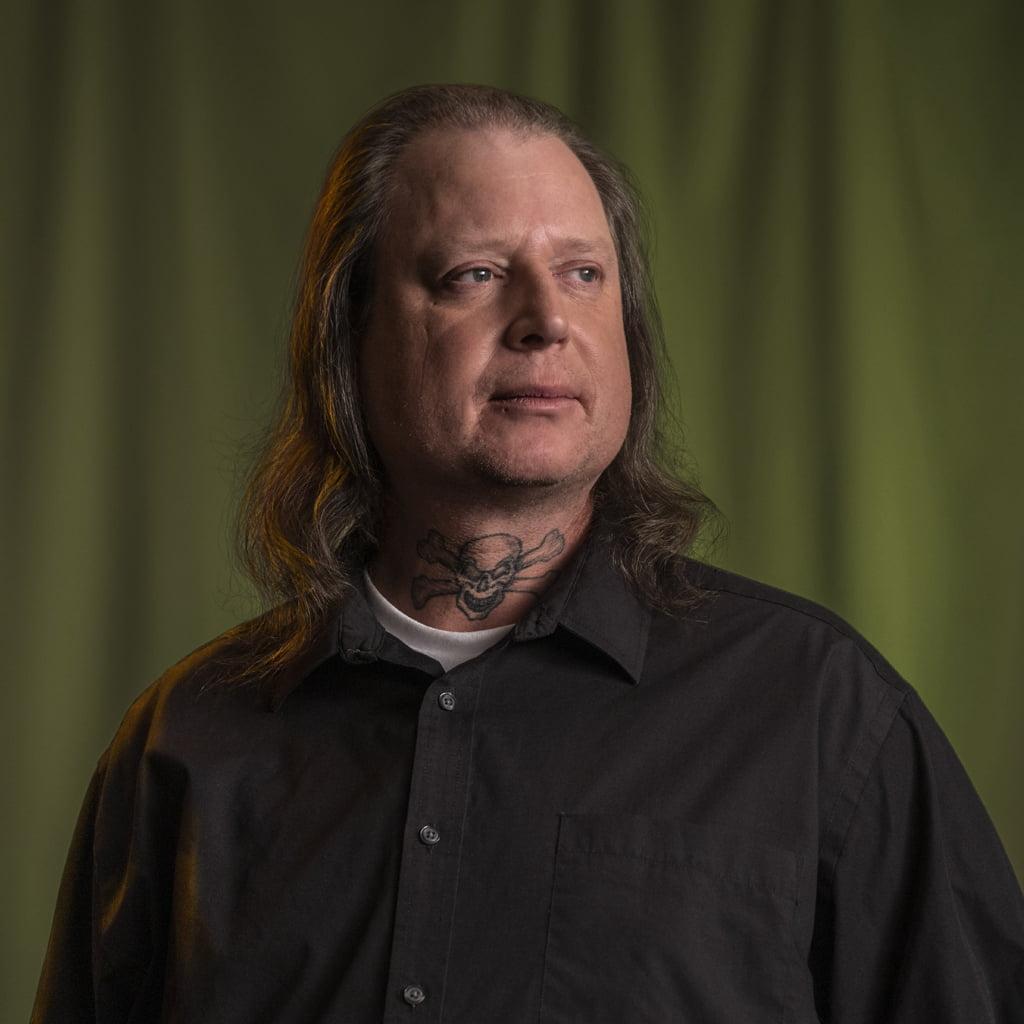

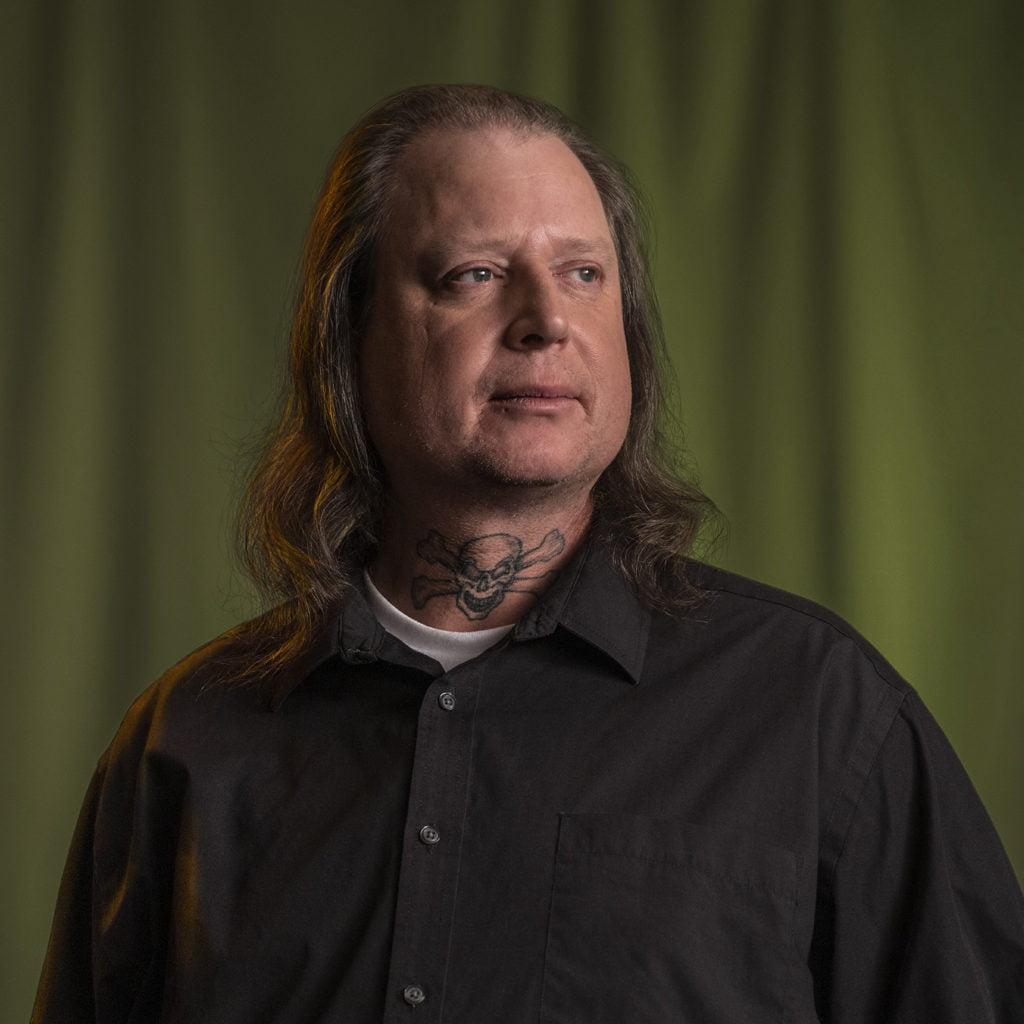

BRYAN | Peer Support Navigator

Patience can be hard when you have a loved one struggling with addiction. But meeting people where they are at is critical.

I struggled with heroin addiction for 22 years. Along the way, I overdosed ten times, lost friends, and saved a lot of lives. It’s been a long, challenging journey, but I’ve come out stronger on the other side. Most importantly, as a Peer Support Navigator, I am helping others find recovery and, in some cases, helping them avoid some of the hardships I’ve experienced.

As someone with a lot of experience with overdoses, I have seen firsthand the importance of naloxone. It’s saved my life, and I’ve administered it to save lives. Because it’s effective, risk-free and easy to use, we must try to get this in the hands of everyone.

Medications aren’t the only things that save lives. Our attitudes and language play a huge role as well. It’s essential to avoid stigmatizing terms that leave people feeling hopeless or thinking less of themselves. Tone and presence are important too; remaining calm, understanding and listening more than talking builds trust and leaves the door open for people who may not be ready to take the first step.

Patience can be hard when you have a loved one struggling with addiction. But meeting people where they are at is critical. In my experience, people will get help when they’re ready. You can’t make them quit and you can’t rush them to it.

When someone is deep in their addiction, it can be hard to get through to them. So, it’s best to give them time and be their cheerleader by recognizing all the good things they are doing.

VICTOR | Peer Recovery Coach Manager

In peer recovery, everyone is a person first.

My journey to becoming a peer recovery coach started while I was still in jail. I was enrolled in a few programs, and one of those introduced the peer support program. I knew I wanted to change my circumstances, so I applied to be a peer recovery coach while I was still in jail. The organization I applied to told me to get in touch when I was released. It took a while, but eventually, there were some free training sessions available, and that’s how I got my start. It gave me a chance to make a career for myself in a situation where it can be hard to find opportunity.

Peer recovery coaching was introduced in Colorado around 2015, so when I started it was in its infancy, and that was tough because we didn’t always have the support or recognition we needed. The good news is, I was able to shape the program because it was so new. I had the chance to go from a peer recovery coach to overseeing other coaches and directing grant funding for peers.

There’s so much stigma around substance use disorder and recovery, so our language is critical. In peer recovery, everyone is a person first. Labeling someone by their diagnosis is one of the most dehumanizing things you can do. They’re not an “addict,” or defined by their addiction.

We talk a lot about being an advocate – with a little “a” and big “A.” The little “a” is what you do for your clients: speaking to those struggling, getting them in the door, and helping them advocate for themselves. The big “A” is about advocating for changing the system. That part is about improving the structures in place to help those struggling with substance use disorder and, in my case, advocating for more tools, training, and resources for my fellow peer recovery coaches.

As a peer recovery coach, you have to be a good role model. Your actions have a ripple effect. When you’re a peer recovery coach, you aren’t just helping one person at a time; you’re positively impacting everyone in that person’s life. When the community sees your success and effort to help others, they want to invest, so being a good role model has this snowball effect.

The evidence is out there that peer counseling works, which can have this multiplying effect. Supporting this line of work is one of the best tools we have to help people with substance use disorders.

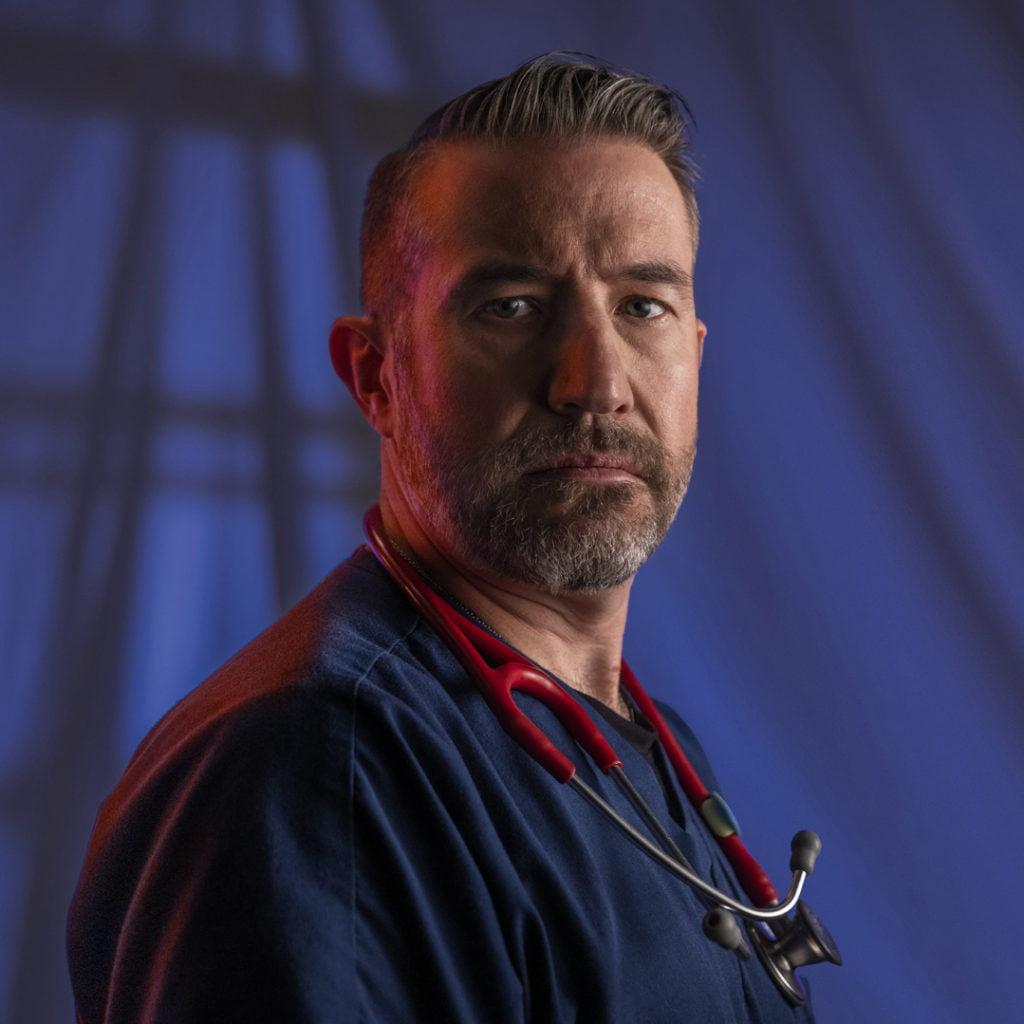

SHERIFF JAMIE FITZSIMONS | Summit County, CO

As law enforcement officials, our job is to protect life. Isn’t offering life-saving treatment an extension of that sacred duty?

I’ve been in law enforcement for over 32 years. In the beginning of my career I spent some time on an undercover narcotics team, and that’s where I first recognized how ineffective our approach was. Arresting and prosecuting people struggling with substance use disorders wasn’t helping those individuals, their families, the communities they lived in or the overall drug epidemic. Today, I serve as the Sheriff of Summit County, where I use what I’ve learned to improve the lives of people with a substance use disorder rather than punish them.

Rather than criminalizing addiction, we need a multi-pronged approach. We still need to address the flow of illegal substances into communities. But we also need to practice harm reduction by offering medication, counseling and naloxone.

As an elected official, I’ve introduced some programs I believe have made a big difference in my community and in people’s lives. As a county, we’ve given Deputies naloxone, allowing them to save lives in overdose situations. We have a program in our jail that provides medications and therapy to treat addiction, giving people a chance to fight their addictions and become whole. We also have a robust co-responder program: an initiative to pair Deputies with mental health professionals for certain calls, bringing safety and mental health expertise to the field. This program has been successful in stabilizing people in the community and getting individuals the help and treatment they need.

If you are a law enforcement leader, getting community buy-in for these programs is essential. Working with community leaders and experts in the treatment, mental and public health fields will make your programs more effective and inclusive.

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to treatment. Just like we have established in mental health, there should be no wrong door for people struggling with substance use disorders to get what they need. Having a range of options betters your chances of getting people the help they need.

As law enforcement officials, our job is to protect life. Isn’t offering life-saving treatment an extension of that sacred duty?

KORY | Emergency Department Clinical Nurse Manager

You can’t rush someone into treatment when they’re not ready, so find a small way you can help them at that moment and leave the door open for the future.

I took an unusual path in this field; I started as a firefighter, which connected me to the first responder community and eventually led me to work in the emergency department (ED) as an EMT. I felt a sense of purpose immediately and went to school to become a nurse. Working in the ED, I saw the extent of the opioid crisis. People came to us for help, but we lacked the resources, process and institutional knowledge to help. That’s how I got involved in using medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) as a form of treatment. The more I learned about it, the more I saw its efficacy and the positive benefits on patients as they found treatment and recovery.

Seeing the power of MOUD firsthand is incredible. These patients have been fighting for their lives, struggling to give thought to anything else. The first time they receive these medications, they start thinking about their lives again, their health and their futures. When we started giving these medications, some colleagues said, “Won’t they just keep coming back?” Yes, they’ll come back and get the help they need. I felt this was a good thing. Today, attitudes are much different. Many doctors and nurses see the benefits and treat substance use disorder the way they would treat anything else. But there are still minds to change.

Having done this for a while, the advice I would pass along to other nurses is that you have to meet patients where they’re at in life. You can’t rush someone into treatment when they’re not ready, so find a small way you can help them at that moment and leave the door open for the future.

As a society, we created the stigma around substance use disorder. So, it’s our responsibility to overcome that stigma, especially by helping people understand their unconscious biases.