Explore Colorado Stories

Addiction can affect anyone, regardless of race, gender identity, age, geographic location, sexual orientation or income. Recovery is possible through the support of community, and when loved ones recognize and end the shame and judgment of substance use disorders.

Watch and read Colorado stories about individuals who broke down the barriers to treatment and overcame stigma to find recovery for themselves or loved ones.

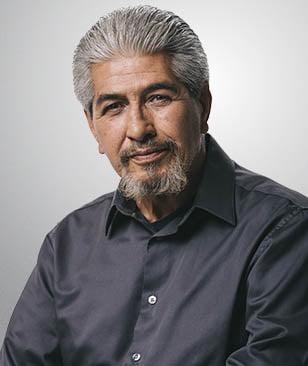

Jack | Sedgwick, CO

“For me, farming taught me grit, strength, and never giving up—all traits that have been crucial in my recovery from addiction.”

My name is Jack, I’m a third-generation farmer and rancher from northeastern Colorado, and I am in recovery. I raise cattle for a beef operation on about 300 acres. Farming and ranching have always been a big part of my life, and what I love most is the freedom. We’re all neighbors here, and we should be looking out for one another. That community connection is vital, especially in tough times.

Growing up, I started drinking in my teens. It was part of the small-town culture—a way to fit in. But alcohol eventually became more than just a social activity as the pressures of agriculture work began mounting. Over time, alcohol use took hold of my life, and I became isolated. The shame and guilt of my addiction weighed on me, but I kept pushing through. For a while, I was just living day-by-day, struggling with depression and anxiety. I would pray every night, begging for help. I couldn’t keep living this way.

The hardest part was admitting I needed help, especially in a rural community. With the lack of services and the overlooked mental health struggles in agriculture, our need-to-be-tough mentality often overshadows our need for support. We don’t talk about addiction in agriculture; we’re taught to be tough and keep going. But I knew I needed to get help or I was going to die. So I started researching and looking for support. Finding help wasn’t easy. Treatment services were 45 miles away. In the first three years of my recovery, I drove over 120,000 miles for services and therapy. But it was worth it. I found my therapist, who pushed me further, encouraging me to keep seeking more support.

The hardest part was the mental battle of learning how to cope without alcohol. It took months, even years, for my mind to fully heal. But through the 12 steps program and therapy, I began to find stability. Now, after over six years of sobriety, I know what it means to live free of addiction. It’s not easy, but it’s worth it.

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned from both farming and recovery is to never give up. Even when things seem impossible, you push through. You keep going. I’ve become a peer support specialist to help others because I want to be the person I needed when I was struggling. If you’re out there, stuck in addiction, just know: recovery is hard, but it’s worth it. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. You’re not alone, and you’re worth it.

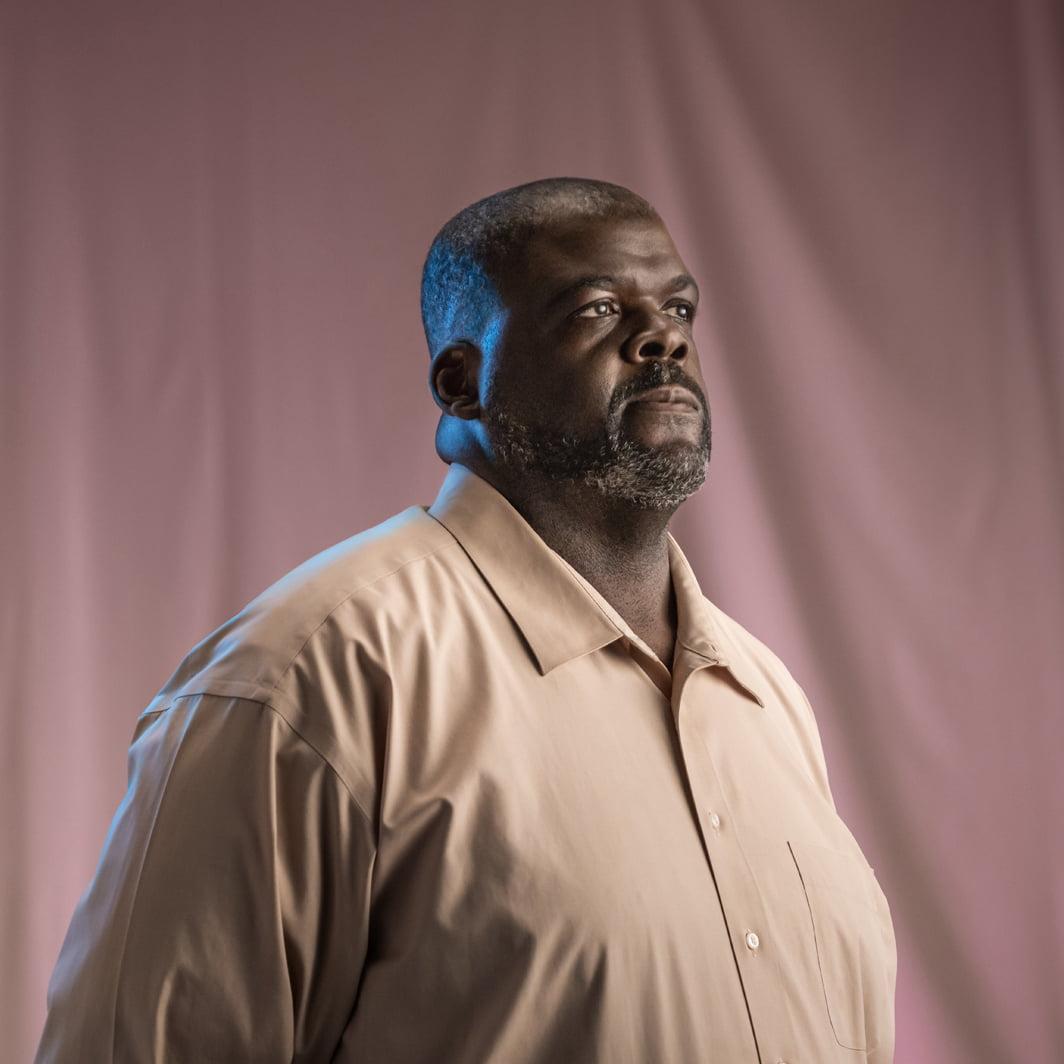

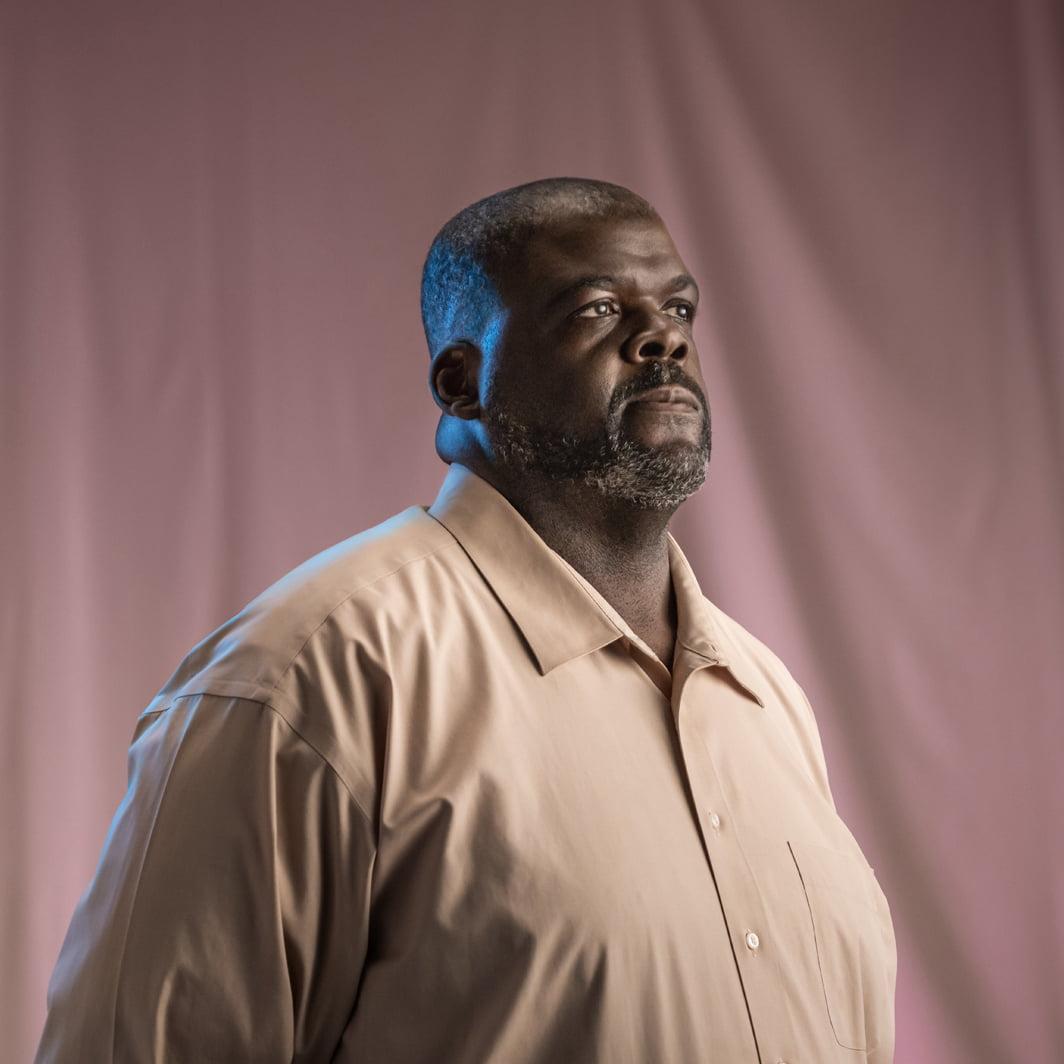

Brian | Grand Junction, CO

“Recovery means consistency and accountability; to yourself, your loved ones, and anyone who cares.”

My name is Brian, and I am in recovery. I moved to Grand Junction in 2004, but I’m originally from Texas. Growing up, I lost track of what really mattered. At 13, I started hanging out with the wrong crowd, drawn to heavy metal music and drugs. For years, I didn’t even know help was available. I kept running from my problems, only to end up right back where I started.

Everything changed when I was in jail after a drug raid. A Meth Task Force Agent asked me a simple question: “Do you want to keep living this way, or do you want something better?” That’s when I knew I had to make a change. He offered me the opportunity to be the first person to attend their new treatment program in Mesa County. I didn’t realize it then, but that moment led me to the start of my recovery journey.

When I came to Grand Junction, it felt different—it felt like home. Recovery isn’t just about quitting drugs; it’s about staying consistent, setting goals, and building a new life. That’s why having people who believe in you is so important. That’s why having people who believe in you is so crucial. One of the coolest full circle moments I’ve experienced in my recovery is that the Meth Task Force Agent who helped me get treatment is now the Mesa County District Attorney and I have the opportunity to serve on the board of a community corrections program alongside him.

For me, my family has been my biggest support. My wife and kids have stood by me every step of the way, even when I didn’t believe in myself. They’ve helped me stay grounded and reminded me that I always have a safe place to return to.

Martial arts has also been key in my recovery. It gave me discipline, focus, and a way to channel my energy. Addiction takes up so much mental space, and martial arts helped me fill that space with something positive. It taught me how to face fears, be consistent, and rebuild my confidence.

Recovery is tough, but it’s possible. It’s not just about quitting—it’s about rebuilding your life. For anyone out there struggling, remember this: recovery isn’t easy, but it’s worth it. With the right support—whether from family, friends, or a community that believes in you—you can do it. Don’t give up. A better life is waiting.

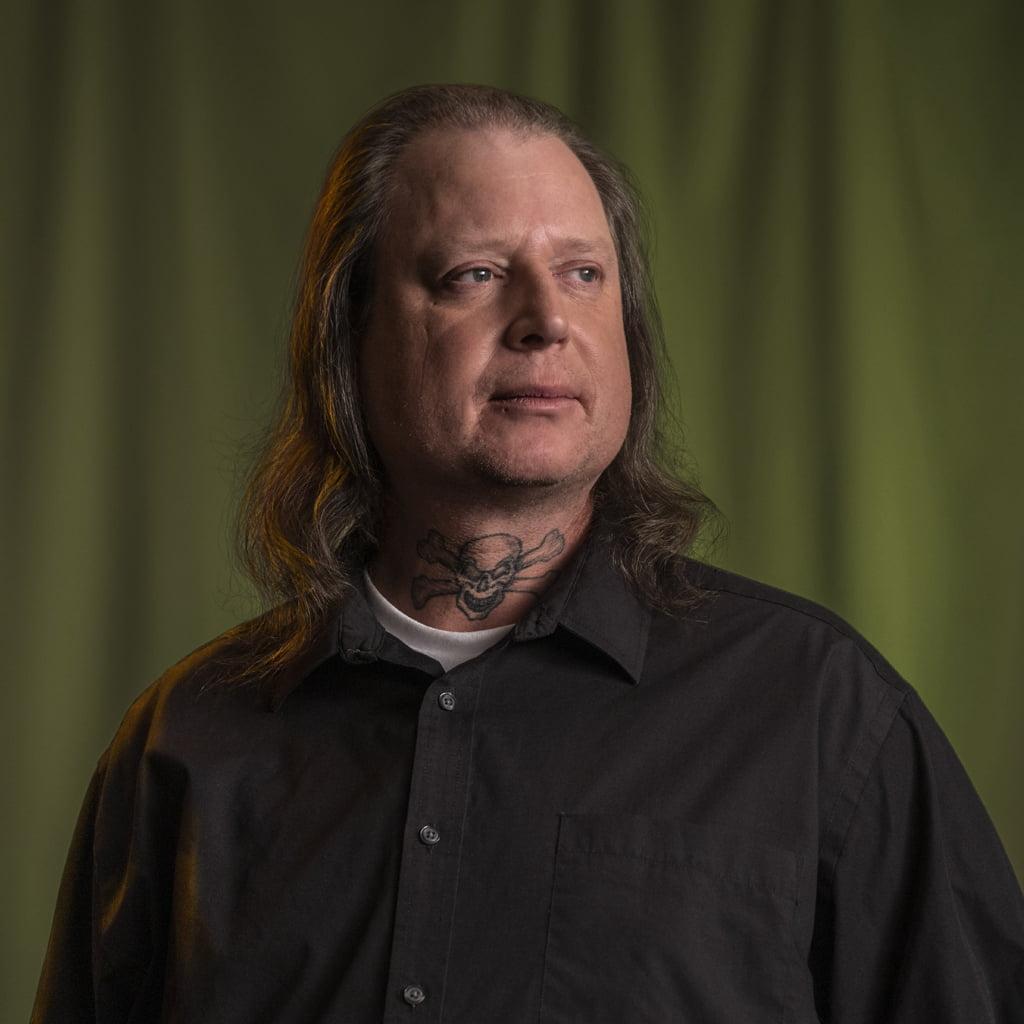

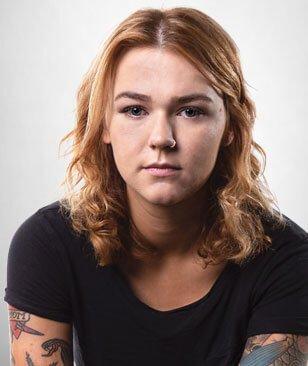

Saxon | Craig, CO

“Don’t isolate yourself—do what’s best for you, whether that’s medication or treatment. Find what works for you.”

My name is Saxon, and I am in recovery. I grew up in a home where addiction was a part of everyday life. Both my parents struggled with substance use, and the environment I grew up in shaped my own experiences with drugs. At just 13, I started using alcohol and pot, and by my late teens, opioids became my escape. The pain and trauma from my childhood led me to a place where using felt like the only option.

After years of battling addiction, I came to realize I couldn’t keep living this way. Accessing treatment was a constant battle. Financial barriers, lack of insurance, and a shortage of facilities willing to take me and my children made it seem impossible. For a long time, I feared I would never find the help I needed. When I found a treatment center in Steamboat, it felt like a glimmer of hope, but the struggle didn’t end there.

I was able to find recovery through my treatment program in Steamboat, but my journey to recovery was definitely not linear. Eventually, I also discovered medication for opioid disorder (MOUD), and it changed everything. I began taking a monthly injection that helped me regain control over my life. It allowed me to help my brain return to balance and I became more motivated, present, and able to focus on my children and my work. It helped me find balance, and I felt like the dark cloud that had followed me for years had finally lifted. I am now a strong proponent of harm reduction which includes MOUD, naloxone, test strips, etc.

Living in a rural community like Craig, and so near to mountain communities like Steamboat, presents unique challenges for those in recovery. The party and vacation culture of mountain communities can be hard to overcome, and the stigma surrounding addiction is real—resources can feel out of reach. But I’ve learned that recovery isn’t a one-size-fits-all journey. It’s not about doing everything perfectly or following a set path—it’s about finding what works for you. Medications have been an essential part of my journey, and I believe it saves lives, especially in places where addiction is widespread but support is limited.

If you’re struggling, know that there’s hope. Recovery is possible, and medications could be the key to helping you reclaim your life. You don’t have to do it alone—there’s support out there, even in rural communities. Keep moving forward, no matter how small the steps may seem.

Tom | Lakewood, CO

I found that when I need support I just need to speak up and talk about how I’m feeling, what I’m going through, and how it’s affecting me.

I grew up in West Omaha, Nebraska, and life took a drastic turn when I lost my father to cancer at 13. His death hit me hard, and by 15 or 16, I turned to marijuana to cope. It wasn’t long before I discovered opioids, and addiction quickly consumed me. I spiraled from recreational use into addiction. I kept searching for a way out, but the addiction only pulled me deeper.

For years, I tried to handle it on my own, but nothing worked. Eventually, I found help at an inpatient treatment center, which was a life-changing experience. I had no idea such places existed or how they could help. I had always thought my life would end in death or jail, and I’d never seen anyone recover. But learning that recovery was possible gave me hope for the first time.

After rehab, I still struggled, even though I had some time in sobriety. It wasn’t until I found the 12-step program that lasting change began. The turning point came when I realized the damage I’d done to my relationships. My family didn’t trust me, and I had no real connections. I was homeless, unemployable, and couldn’t function in society. That’s when I realized I needed to do something different.

Staying sober has been harder than getting sober. Life doesn’t stop, and I had to face many of life’s circumstances without turning to substances. I had to take responsibility for my well-being, something I’d never done before. Breaking the cycle was crucial, in-patient treatment played a key role and ultimately set me up for success.

The most rewarding part of recovery has been helping others. Through recovery, I’ve walked others through their recovery and helped them find long-term sobriety. It was a position I never thought was possible, but others saw the change in me and saw me as a leader. The ability to give back what was freely given to me has been incredibly fulfilling. Everyone’s journey looks a little bit different, and there is no right or wrong way to recover—what works for one may not work for another. I’ve learned that owning your experience and sticking with what works for you is key.

Dara | Aurora, CO

“Choosing to better myself meant facing the struggle of being open, realizing that healing requires letting go of my walls and seeking the help I needed.”

I grew up in a happy household with family support, but having immigrated from Mexico when I was young, I faced a lot of feelings of being left out because of cultural isolation. I started using drugs here and there as a teenager, but things changed when I got involved with someone deep in addiction. I became addicted, and it started taking over my life. I did things I never imagined. I couldn’t understand why I was choosing substances over everything else. It wasn’t until I lost everything and ended up in prison that I realized I needed to change.

In prison, I reflected on my life and struggled with expressing my feelings. Talking about emotions isn’t common in the Latine culture, so being open about my pain was hard. When I decided to get sober, my reluctance to share became a barrier to my healing. Over time, with the help of a community center focused on providing activities and connection in recovery, I learned that seeking help and being open to therapy was a strength, not a weakness. It’s still challenging, especially in my culture where seeking help can be seen as a sign of weakness. But I’ve come to understand that healing requires breaking down those walls and embracing things that feel unfamiliar.

Recovery also taught me how addiction affects our bodies and minds. Long-term substance use changes the brain’s chemistry, making it harder for the body to work. Early recovery is a healing process, and it’s natural to feel anxious or low on energy. Without the support from medication, it can be easy to feel isolated and depressed. For me, medication was crucial for my recovery and helped restore balance, giving me the energy to work, attend meetings, and stay connected. With the right help, recovery became more than just a dream.

Now, I’m lucky to work as a bilingual recovery coach, helping others. I’ve seen how important it is to provide support in both English and Spanish. Many people in my community face language barriers and don’t know where to turn for help. I offer guidance that’s culturally relevant, understanding their unique struggles. I can relate to their struggles and want to be there for them the way I wish someone had supported me. In recovery, building connections is everything. It’s about finding people who can understand and support you. Reach out, make connections, and don’t be afraid to ask for help when you need it. Saying “I need help, and I need it today” is a powerful step in your journey. The right connections can make all the difference.

Vanessa | Thornton, CO

“In recovery, I’ve learned that all my journeys—mental, emotional, and substance recovery—need equal attention, and I need to be as willing to accept love and compassion as I am to give it to others.”

My substance use began in my early 20s. I worked as a bartender and played music, which provided attention and the drugs gave me a way to mask the pain of not fitting in. This continued for years, eventually leading to time in prison. After serving four years of a 10-year sentence, I focused on myself, learned to love who I truly was, and began my recovery journey.

A pivotal moment inside prison changed everything. An older inmate told me to focus on myself, reminding me that the only thing that mattered was my inmate ID number. That moment led me to realize I didn’t need to please anyone but myself and to prioritize my recovery over everything.

In 2019, after realizing I had lost everything—family, connection, trust—I began to focus on my recovery. Yoga helped me shed my ego and start healing. My journey was about reclaiming my authentic self, and when I transitioned to become Vanessa it was a powerful turning point. I finally embraced who I was and began to truly love myself.

The recovery community is where I found unconditional love and acceptance. People in recovery often feel defeated, but once we start healing, we return that love. When I transitioned, I feared I’d lose the connections I had built, but the opposite happened. I was accepted, and it empowered others in the community to embrace their own truths.

In early recovery, I struggled with boundaries, often going above and beyond for others. But I learned that coddling people can harm their recovery. Many of my close friends didn’t set boundaries, and I lost them. Now, I make sure to focus on my own foundation first, balancing all aspects of my recovery, including mental health and trauma.

My passion now lies in helping others on their recovery journey, speaking about my journey, and encouraging others to step into their truth. I believe our voices are powerful, and when we listen with our hearts, we see people for who they truly are—not their race, gender, or background, but as humans deserving of love, acceptance, and a second chance.

Michaela, Sterling, CO

“There are many pathways to recovery.”

I started to party in my early 20s. It wasn’t long before I was using cocaine every day. I tried to escape the party lifestyle by moving away. Unfortunately, I had a boyfriend who introduced me to meth. It didn’t take long for me to lose everything, including jobs, housing, and, eventually, custody of my son. I experienced homelessness and incarceration, eventually spending 30 days in jail.

A judge mandated my release as long as I went to live with my parents. My parents didn’t understand a lot about addiction. But, they were supportive and willing to learn. This support was critical despite a few returns to use. My mom even wrote letters to the judge begging them to send me to treatment. The judge actually ended up ordering me to go back home and live with my parents. From there, I found a peer coach who gave me the strength to believe in myself. Once I saw what life could be like, I never found any desire to use substances again.

Today, I have nearly four years in recovery, which has given me the ability to help others as a peer recovery coach and gain full custody of my son again. I’m getting married, and I have rediscovered parts of myself again that I had lost in active addiction. I get to be alive, I get to be free. I try to share my experiences and hope by advocating for those who cannot advocate for themselves. The best advice I can give to those struggling with addiction is to love yourself and not let shame keep you from the help you deserve. If you’re struggling, there are people who care. Don’t struggle alone.

Valentina, Montrose, CO

“The recovery community walks alongside me on this healing journey.”

My relationship with substance use began at an early age. I grew up in a household where alcohol was always present, and I tried alcohol for the first time at age five. After experimenting with substances throughout middle school and high school, I moved out at 17 and ended up living a “party” lifestyle. Although I was using substances, I was able to keep my life together for a while. I was also in the midst of a codependent and unhealthy relationship while also struggling with anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation.

At the time, I had a friend in recovery who was in a sober living situation. She just so happened to call on me on one of my darkest days. At first, I wasn’t being honest with her, but after she created a safe space for me, I was able to express a lot of what I was going through. She said I was deserving and worthy to live this life. And that I should ask for help. That moment was such a big relief for me. It inspired me to choose life. From there, I was able to get in touch with a 12-step program, where my journey to recovery from alcohol and polysubstance use started. The recovery community played a really strong role in my story. I experienced a lot of loss in a very short amount of time. It was tempting to numb myself, but the recovery community was able to support and empower me through the grief.

Recovery has taught me how to love myself and others with substance use disorder and how to create healthy boundaries while offering hope. One of my goals in recovery is to offer my time to others in need, provide hope, and encourage change. For those who are still struggling with active addiction, embrace the light and push out the darkness of addiction.

Candice, Durango, CO

“Supportive communities provide the fundamental connections all humans need. A beacon of hope, actively dismantling the barriers of stigma surrounding addiction.”

I struggled with substance use in my teenage years. My use began as a tool for me to fit in, to feel like I belonged to a community. In time, it became a coping mechanism, often looking to alcohol when things were difficult, which caused a lot of negative impacts in my life. I found myself at age 26 going through the cycle of losing everything, and finally it came to the day where my partner set a boundary in our lives that I needed to get help, or I would be out of his life and out of a home. Around that time, I spotted a brochure for an employee assistance program in my company’s break room. This free resource provided me access to therapy, where I was encouraged to attend recovery support meetings.

Initially, I hesitated to attend a meeting in my small town because I was scared of being judged, but my partner accompanied me, and the overwhelming support and love I received from the group was amazing. All of my fear went away when I walked into the room. Everyone was genuinely happy to meet me.

After engaging in a traditional program of recovery for several months, I was inspired to explore the broader realm of recovery. I discovered a wonderful community that encouraged me to define recovery for myself and forge a path fit for me. Around this time, the loss of a close friend to an overdose deepened my commitment to the recovery community, both for my own healing and to support others. Discussing loss and working to shift the stigma and language around addiction became crucial components of my recovery journey. My partner was an incredible support system—he gave up alcohol before I did, supported me when I had a return to use, and was very patient with me.

Today, I remain deeply involved in the community as a leader in a Recovery Community Organization. One of my favorite things about my recovery is the accountability I developed in the process. I love being a person that my family, friends, and neighbors can count on. I follow through when I commit to being there for someone. I’m responsible for my actions. I am honest with myself and the people around me. Most importantly, I am accountable to myself, knowing my capabilities and limits, yet pushing my comfort zone to continually grow as an individual and a community member. This dedication isn’t just about supporting others; it’s the fuel that moves me forward, sustaining my ambitions and propelling me along the path of recovery.

Julie | Lakewood, CO

“My son realized he didn’t have anything to be ashamed of.”

I suspected my son was experimenting with drugs in high school, but never confronted him. Part of me didn’t want to know. In college, it became harder to ignore; he wasn’t himself anymore. When I finally confronted him, he admitted to using heroin and it was a very hard concept to swallow. He agreed to rehab, and we checked him into an inpatient program the next day. Over time, he helped us piece together how he’d gotten addicted to opioids: it all started with pain pills prescribed to others that he’d steal from medicine cabinets. Eventually, he moved to heroin as it was cheaper and easier to get.

He did inpatient rehab for months and has been in recovery, and taking Suboxone, ever since. Unfortunately, he still experiences prejudice after all these years when he mentions he continues to manage his recovery with medications. I realize now that my son was experiencing a lot of shame about his addiction, especially while in rehab, and a big part of his recovery was therapy; talking to others who’d been through the same thing. My son realized he didn’t have anything to be ashamed of.

The same held true for me: talking to others about what I was feeling gave me strength to face what he was going through. I feel beyond lucky to have my son back, doing well and living his life.

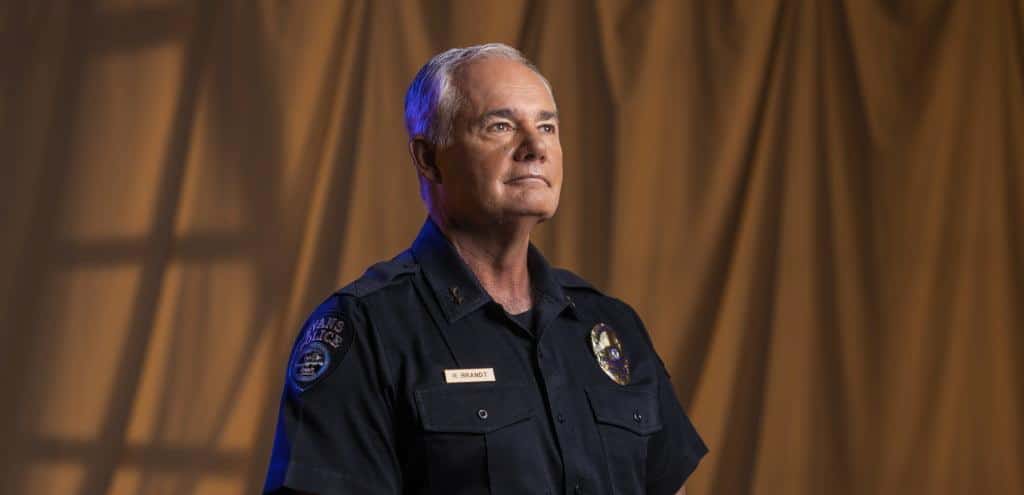

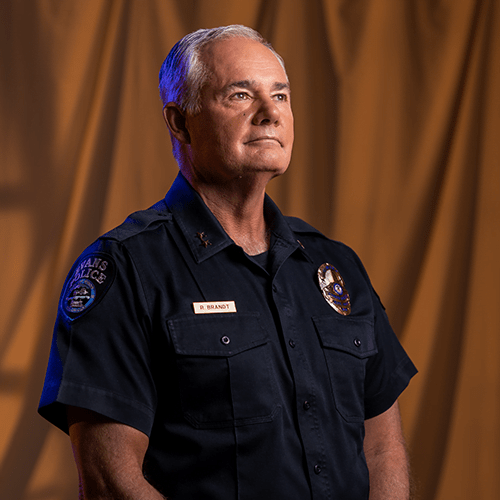

CHIEF RICK BRANDT | Evans, CO

“I remind them that they took an oath to protect life. Naloxone does just that.”

I’m Chief Rick Brandt. I’ve worked in law enforcement for over 40 years. Currently, I’m serving as the Chief of Police in Evans, CO.

I always knew I wanted to help people, and I thought the best way to do that would be as a police officer. My journey in law enforcement started in Aurora, CO, where I started as a regular officer and eventually worked my way up through the ranks.

Over the years, my attitudes toward addiction, incarceration, and rehabilitation have changed. My father struggled with addiction, and I couldn’t understand why he didn’t give it up. But a few things happened to me along the way. First, I was given a prescription for opioids after surgery and after just a few days, I could feel cravings. That was really eye-opening and helped me understand how addiction can begin for some people. More importantly though, I saw how locking people up for their addictions wasn’t helping them on the individual level and wasn’t having an impact on the larger community or the addiction crisis.

So, I dedicated my career and my energy toward shifting attitudes within police departments, encouraging policy change, and educating people on how to combat the opioid crisis. I’m a big proponent of a co-responder program. Rather than sending an officer alone, we advocate for sending someone who works in mental health or the recovery field along with the officer to respond to calls where a mental health resource might be needed. These professionals can offer resources and treatment options that can lead to real change rather than incarceration. I’m also a big supporter of offering programs to provide treatment using medications for opioid use disorder in jails, giving people the opportunity to access treatment so they can start fresh when they are released. Lastly, I’m an advocate for supplying first responders, especially police officers, with naloxone. Naloxone is a life-saving opioid overdose reversal medication. Law enforcement professionals often arrive first on the scene of an overdose. Putting this medication in officers’ hands can save someone’s life. Some people in the policing community resist this. They have a mindset of, “why am I saving someone who makes such risky decisions over and over?” To those folks, I remind them that they took an oath to protect life. Naloxone does just that. You can save their life and give someone a chance to find recovery.

KYLE | Fort Collins, CO

“You can do this; you are capable.”

My earliest experience with addiction was with my mother. She drank heavily, eventually passing away from cirrhosis of the liver. I was in middle school, and her death hit me hard. That’s when I started experimenting with substances throughout middle school and high school. My substance use got more serious after high school. At the time, I just felt like I was living life and having fun. It didn’t seem out of the ordinary. But as I got into my late 20s, I realized I wasn’t reaching my goals or potential; I didn’t feel like I was doing the things I wanted to do in life.

My addiction eventually led to incarceration. When I was first locked up, I thought I would just get out and keep doing exactly what I was doing. But having time to sit, I could reflect with a clear mind for the first time since I was a kid. And I just had this moment where I felt like, “I’m done with that.”

My goals were something that helped guide me. I started small: my first goal was to stay out of prison. A friend reminded me, “You have to have something else. Your goal can’t just be not to come back.” And that’s when I started to believe I could do things. I could set goals and attain them.

Today, I’m working on general studies for my undergraduate degree in social work, but the plan is to get a master’s degree in the same field. As a recovery navigator for a Colorado agency that serves people experiencing homelessness, my job is to offer recovery resources to those seeking change, as well as help curb recidivism by guiding people to education, employment, and housing resources.

I think some people don’t seek treatment for the fear of change. To those folks, I say, “have no fear”. A lot of people have left that life, myself included. You can do this; you are capable. Friends and family members of those struggling with addiction are victims too, and I try to remind them of that. So, I always try to offer as many resources and options as possible to those friends and family members. And I remind them that boundaries are healthy for themselves and their loved ones.

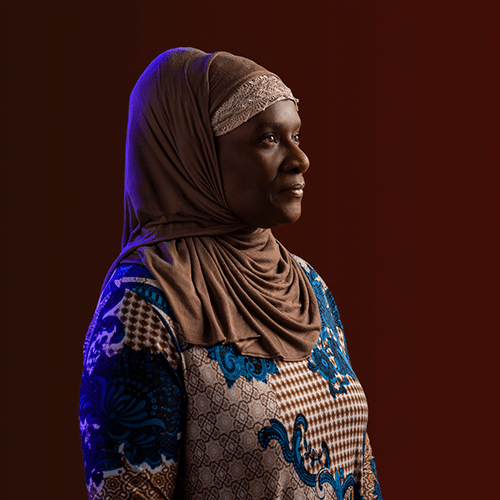

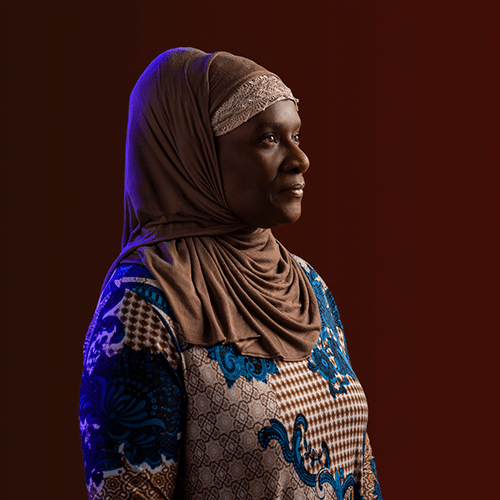

Hawa | Colorado Springs, CO

“I want them to see that the past doesn’t have to control the future.”

I’m originally from Liberia, Africa, but I’ve lived in Colorado Springs for the last ten years. I work with children with behavioral troubles, but I also do a podcast and have a charitable organization.

My experiences with substance use come from my father. He had strict parents who felt a lot of pressure to keep up their appearances as a respectable family. Because of that, my father’s struggles with alcohol were never really addressed early on.

His addiction grew stronger and stronger. By the time I was born, he wasn’t around much, and I rarely saw him when he wasn’t using substances. He often stole to support his addiction. A formative memory for me was when he sold my school uniform on the day of a big test. I couldn’t take the test—it was hurtful to have my father do something like that.

Eventually, I moved to America. Although I didn’t have a lot of contact with my father, I tried hard to have a relationship with him. I would call him on his birthday and tell him that even though other people had turned away from him, I hadn’t. Before he passed away, I sat down with him to tell him how I felt and how he had hurt me. He wasn’t ready to hear it or to take ownership, but I was glad I expressed myself.

I have turned a sad story with my father into something positive. Today, I do social work with children and families in the community, and am pursuing a mental health license to be fully equipped to give families resources. I also raise funds to sponsor young people in Liberia struggling with addiction. We help them seek treatment and even help fund school and job training. I encourage them, and I share my story. I want them to see that the past doesn’t have to control the future. I tell them, “your story doesn’t define you.”

HANS | Greeley, CO

“If you’re still struggling with substance use, take your time. It’s not going to happen overnight.”

My substance use started at a young age. I had a lot of older friends and very little supervision. Eventually, I found myself using methamphetamine, or meth. Sometimes, it was to stay awake for work; other times to party. It started to take over my life. I had periods of recovery where I could stay away from it. But then, something like a bad relationship would cause me to use again.

A big turning point came after I made a mistake while injecting meth. My hand swelled up huge. I ended up in the hospital with doctors telling me I might lose my hand. They were able to save my hand, but that experience scared me. I knew I didn’t want to live like that anymore, letting down my kids and parents. And I got a rare opportunity. Because I was healing in the hospital, it was like a detox in a safe environment. I used that safe space and my faith to create positive change in my life.

Now, I’m a peer recovery specialist for a health collaborative in Northern Colorado. My lived experiences have made me a good advocate and helping hand for others. I get what someone is going through, what they are struggling with, what they fear, and what they need. And because of that, I’m able to be effective. I don’t pressure people. I just let them know the resources are here – I’m here – for them when they are ready.

If you’re still struggling with substance use, take your time. It’s not going to happen overnight. You might quit in one day, but recovery can last forever. It’s hard for family members to hear this, but if you have a loved one struggling, ask them to call you when they feel like they’re going to use. Right now, you don’t have control over what people do, but if they know you support them at their worst, you will support them at their best.

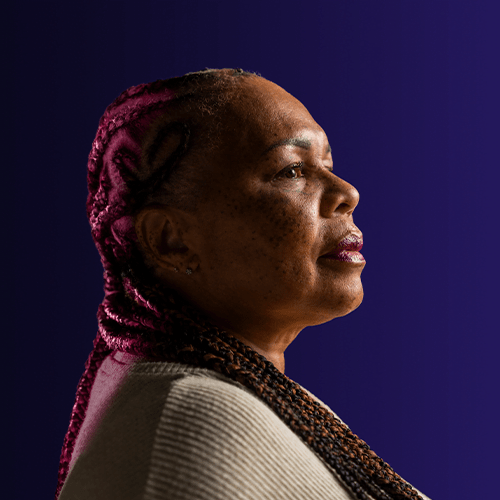

JANICE | Denver, CO

“Don’t be afraid to ask for help, and don’t be afraid to offer it.”

When I was a kid, I looked different from everyone else. They made fun of me, and I spent a lot of time alone. When I got to high school, I wanted to fit in, so I started smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, and eventually using drugs. Over time, in my 20s, 30s, and 40s, I struggled deeply with addiction to crack cocaine. I experienced homelessness and loneliness, and spent time in and out of the judicial system.

A few things helped my recovery journey. A handful of people in the judicial system cared about me and showed me kindness; some believed in me so much that I didn’t want to let them down. But more than that, it was my spirituality that rescued me. My relationship with God saved me. He was there for me whenever I was in my lowest moments, struggling with addiction, or feeling like I might give in to temptation. I felt as though He made changes in my life and provided guidance behind the scenes to help me find recovery.

Today, I’m a medical case coordinator, speaking in jails to other people struggling with addiction. I use my spirituality and lived experiences to share empathy and kindness with those in need. In recovery, it’s crucial to re-learn what you like. Recovery doesn’t have to be dull. We go to movies, to the park, and have sleepovers. I love to roller-skate—and I don’t mean to brag—but I’m pretty darn good.

When I speak to those still struggling, I try to cover those essential bases. I find out if they have a place to stay and find them one if they don’t. I ask them if they need a job and help them find work. To families with someone struggling, I say, “Call Janice. I’ll help them!” I really will. But if they can’t call me, I would tell parents and even those struggling that we don’t get high alone and cannot recover alone. So, don’t be afraid to ask for help, and don’t be afraid to offer it.

CHRISTINA | Pueblo, CO

“The skills I learned in CRAFT have made a huge difference in our lives.”

My niece is in the early stages of her recovery, so I’m caring for her two children. I refer to myself as an auntie-mommy.

I’ve learned that loving someone in recovery means you have to give them and yourself grace through this process. My niece struggled with methamphetamine use at a very early age. Using such a powerful substance at 16 affected her brain, so she was stunted emotionally. As she’s recovered, I’ve seen her change and grow. There are difficult days for both of us, but I remind myself it’s a process.

I started CRAFT (Community Reinforcement and Family Training) classes during the pandemic. When I logged on, I felt strange seeing all these people I didn’t know. As I heard their stories, I had the ‘aha’ moment, “I’m not alone in this.” There were others out there who understood what I was going through.

CRAFT taught me to speak to my niece in a way she was ready to hear. I learned to wait for the right time to talk to her and when to give feedback. In CRAFT, we call that the “hook.” Learning communication skills and waiting for the right moment are essential.

It’s been a struggle, but I waited for that right moment, that hook moment. And today, I’m happy to say my niece is ten months into recovery. The skills I learned in CRAFT have made a huge difference in our lives.

When you can relate to somebody going through the same thing, you build a bond with people. You know that they’re in that world with you. You can lift each other up, pull each other up when you’re feeling down; there’s that connection.

ANGIE | Colorado Springs, CO

“I encourage family and friends to find their own life in recovery, whatever that means for them.”

I come from a family with a history of substance use. My father struggled with alcohol and prescription drug use, and I was profoundly affected by it. I had my own struggles with addiction and thankfully got into recovery for my substance use and mental health. My idea of recovery has changed so much over the years. I entered recovery through a 12-step program, and now embrace a philosophy of many roads to recovery.

Today, I work as a Family Advocate and CRAFT (Community Reinforcement and Family Training) facilitator, teaching families and friends new ways of interacting with their loved one. With CRAFT, you can make a difference in the life of the person who is using substances. You can’t make them change, but you can support them in a way that invites them to change. Families attending CRAFT can learn how to support their loved ones while maintaining connection with them.

If you’re still struggling, I want you to know that we do recover. The joy of recovery is in the journey, not the destination. I encourage family and friends to find their own life in recovery, whatever that means for them. As Johann Hari says, “The opposite of addiction is not sobriety; it’s connection.” Families are part of that connection. No one recovers alone.

JOANNE | Woodland Park, CO

“We may not solve all the world’s problems, but we might solve just a little of them by helping others.”

My family had a history of substance use disorder. Growing up around it was stressful and emotional. My parents divorced when I was 15, and I struggled with feelings of abandonment. I did a lot of partying in high school, eventually dropping out and I started drinking more and more. I didn’t feel like anybody cared about what I was doing, and so I struggled in my teens and twenties.

I ended up having two beautiful boys in my twenties. When we moved to Colorado, I met my future husband. He had two children of his own. Together, we created one big family. At the time, I was still drinking heavily, but I was still functioning. I was there for the kids at their games, but I drank during their sporting events because I didn’t know what else to do with my life. I had no interest, no genuine interest of my own.

In 2018, I finally had my last drink. I joined support groups and did the work to find recovery. When one of my sons had his own struggles with addiction, it led me to CRAFT (Community Reinforcement and Family Training). It showed me how to help my family and also how to help myself. The communication skills you learn help the entire family.

CRAFT has brought so much to my life, like communicating with loved ones without accusations, being kind to someone in the recovery process, setting boundaries, and caring for myself without taking on the consequences of others.

Today, I’m a part of some support groups, with CRAFT being one of them. CRAFT is open to all friends and families who care for someone who is struggling with a substance use disorder. If you have substance use disorder in your family, there are ways to address it and become the family you need, and want, to be. I think that what the world needs is just openness and vulnerability. We may not solve all the world’s problems, but we might solve just a little of them by helping others.

SARA | In Memoriam

“I didn’t think it could happen to me because a doctor had prescribed them.”

My issue with opioids started in my early 20s after receiving a morphine drip while in the hospital for a medical condition. The drip continued the whole time I was there, and I received a consistent supply of meds when I left. I didn’t realize for another year or two that I probably left the hospital that day dependent on opioid pain medication. In the following years, when I was trying to figure out what was wrong with me and why I was so sick all the time, it was really hard to come to terms with the fact that I was physically addicted to opioids. I didn’t think it could happen to me because a doctor had prescribed them. As my tolerance rose, I needed more and more, and started buying pain medication off the streets. Eventually that progressed to heroin because it was just so much cheaper. I repeatedly sought treatment through my primary insurance provider, but as it’s expensive, they wanted to exhaust every option before giving it to me. Before I could ever get the inpatient treatment I needed, I lost my health insurance, and eventually spiraled back into things. I finally entered into a therapeutic community program in Colorado, and that is how I found long-term recovery. My parents shared my hopelessness and frustration. They were amazed at the lack of options I had when I wanted to get better. Now that our lives are very different, they both rally and advocate for people to gain access to treatment.

RICA | Denver, CO

“What worked for me is not necessarily going to work for the next person, but if you’re willing to try it, then I believe in you.”

When I was 13 I contracted HIV from my father, who sexually molested me. It was believed that he contracted HIV by using needles with his five younger brothers, my father was the eldest of them all and throughout my childhood, I watched four of my uncles and many others get sick and die one right after the other. Watching them go through this horrible experience and die, I told myself, “This is how I’m going to die.” With that mentality, I decided I didn’t need to take care of myself and I started doing drugs, joined a gang and doing everything under the sun to self-destruct, which eventually led me to prison. In 2002, I had my daughter who was diagnosed with Down syndrome. I came to the realization that I was going to screw up her life like my own or it was time to make some changes. I was able to stop using meth, but I was still struggling with opioid usage. At this point, I was raising my daughter and her four half siblings. I knew I needed help, but I felt stigmatized by caseworkers, probation officers and my own family and friends. I felt scared that if I asked for help, they would take the children away from me.

I finally sought out medications for treating addiction, despite some of my family feeling I was just trading one drug for another. At the treatment center, I met someone I could relate to. Marie was the only Brown face in the recovery center that I was able to connect to—she looked like me, talked like me, and had similar experiences to my own. It was because of her that I kept coming back. I might have never found recovery if it hadn’t been for that familiar and supportive woman at the treatment center. I want to pass along what she has done for me, so today I wear many hats in our community advocating for change. I am a certified peer recovery coach and peer specialist who helps empower women living with HIV and people who struggle with substance dependency to educate, support each other and change policy at the levels that impact everyone.

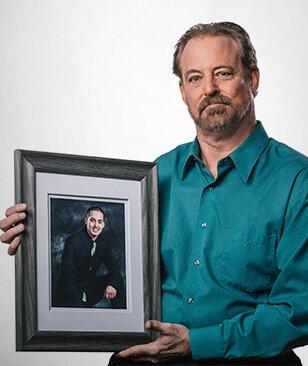

DAN | Grand Junction, CO

“By sharing Preston’s story, I can help others realize they’re not alone.”

My son Preston was a rising football star until he was shot eight times by a gang member outside of our house. He survived, and after visiting the hospital we went to a doctor who prescribed him Oxycontin. We thought the medication was OK if it was prescribed by a doctor, but he kept needing more opioids to manage his pain. He wasn’t himself: getting in trouble at school, wrecking the car. When we realized there was a problem, we got him into a 30-day rehab center where he started taking Suboxone, which helped manage his opioid addiction, but he was still in pain.

We eventually found a solution that made the physical pain manageable, but he still struggled with addiction, emotional pain and PTSD. On June 21 of 2010, he went to the doctor without me and got another prescription for Oxycontin. He passed away the next day. Losing my son was unbearable, but when I started talking about Preston to others, it helped. People hide addiction where I live because they don’t want to be judged. By sharing Preston’s story, I can help others realize they’re not alone. Resources are out there that can help them or someone they know.

DONNA | Behavioral Health Services Director

“More lives have been saved with this medication than any other type of treatment for opioid use disorder.”

I knew I wanted to get into the world of treatment and counseling after witnessing the courage that recovery took, especially with the obstacles like cost and lack of support. It’s why I trained as a therapist and an addiction counselor. This field offers this really rewarding intersection of medical and behavioral health. As the director of Behavioral Health Services for a treatment center, I’m able to interact directly with patients while also managing grants that will have a profound impact on substance use disorder across the state.

There is no single way to help people struggling with a substance use disorder. We are all individuals and we need to be treated this way when it comes to medical issues. We offer our patients options like harm reduction and support programs, as well as medications.

Sadly, stigma exists even within the mental health field. I’ve heard therapists say, “I don’t treat people with addictions because they lie.” First of all, many people who don’t have a substance use disorder lie in therapy. Second, not everyone who struggles with a substance use disorder is going to lie. But most importantly, when you refuse to treat people with substance use disorder, you leave them without essential support. I believe substance use and mental health issues should be treated similarly, especially because they often go hand-in-hand.

Luckily, for behavioral health professionals, the medications for treating addiction are incredibly effective. There is a lot of clinical evidence demonstrating these medications’ effectiveness, especially when paired with other types of support. I tell other professionals that it’s not a cure-all or a miracle drug and that it won’t work for everyone, but when you look at the overall population, more lives have been saved with this medication than any other type of treatment for opioid use disorder.

The fentanyl crisis is staggering. We see it showing up in urinalysis during patient intake, even if they’re not using opioids. It’s essential that we educate people who are using substances, even recreationally. Fentanyl test strips offer one way for people to be informed so they can use safely, an important part of a harm reduction approach.

There’s an unfounded fear that harm reduction or destigmatizing substance use disorder will normalize it. That misconception leads to the idea that we must come down hard on people rather than be empathetic. But this mindset has not proved effective or productive. Instead, we need to acknowledge our fears. When we are responsible for that, we can approach the evidence and data to find the right solutions.

MICHAEL | Lakewood, CO

“People in your life will be advocates for you. They will ask questions and fight for you.”

My family is no stranger to addiction—a close family member has struggled for over 30 years. My first experiences with opioids were in high school at age 14. At 16, my family member could tell I was going through withdrawal and shot me up with heroin. Two years later, I was living in New York City as an escort. This lifestyle was high risk and involved a lot of extreme drug use and some really sketchy situations. I started to get sick—so sick, in fact, that I ended up moving home to Buffalo where I was diagnosed with HIV. Shortly after, I had my first overdose. A friend with Narcan saved my life. Three months later, a second overdose put me in the hospital and served as a wakeup call. My mother was really scared for me. Her fear that I would turn out like my family member motivated me to get better. I started antivirals for HIV and quit using opioids cold turkey. I was lucky. I had family that could help me through recovery, and I had friends who cared about my health and advocated for me. In my story, information was key. When I was diagnosed, I thought I was going to die. But learning about HIV and addiction treatment shed light on hope and allowed me to accept care and help from others. I’m glad I didn’t give up. Today, I’m an addiction counselor, and I share my stories to help others struggling with stigma in both the addiction and LGBTQIA+ communities.

DR. LESLEY BROOKS | Greeley, CO

“I want to break down these systemic barriers, creating easily accessible treatment services that make everyone feel seen and heard.”

I’m a family medicine and an addiction medicine physician, and these two perspectives give me a unique view into the world of addiction treatment.

I come from a full-scope family medicine background, including everything from labor and delivery to pain to substance use. While every part of medicine is equally important, I saw addiction’s impact on black, brown, poor, and marginalized people and families. I thought I could make the biggest impact at the intersection of substance use, mental health, and marginalized communities. There are serious issues with how addiction and treatment are viewed in society and by the medical community. First, addiction is often treated as a lack of willpower, when in fact, it’s a chronic condition much like diabetes. Second, the same structural and systemic inequalities that exist in every other part of society are amplified in addiction and mental health treatment. Treatment can feel non-inclusive for communities experiencing vulnerabilities. People from the Black, Latinx, and LGBTQIA+ communities face judgment and rejection, or find treatment approaches that seem to be made for anyone but them. That’s something I’m advocating to change. I want to break down these systemic barriers, creating easily accessible treatment services that make everyone feel seen and heard. Without question, this is the work that gets me out of bed in the morning, that drives me to spend my days educating, advocating, and building towards change.

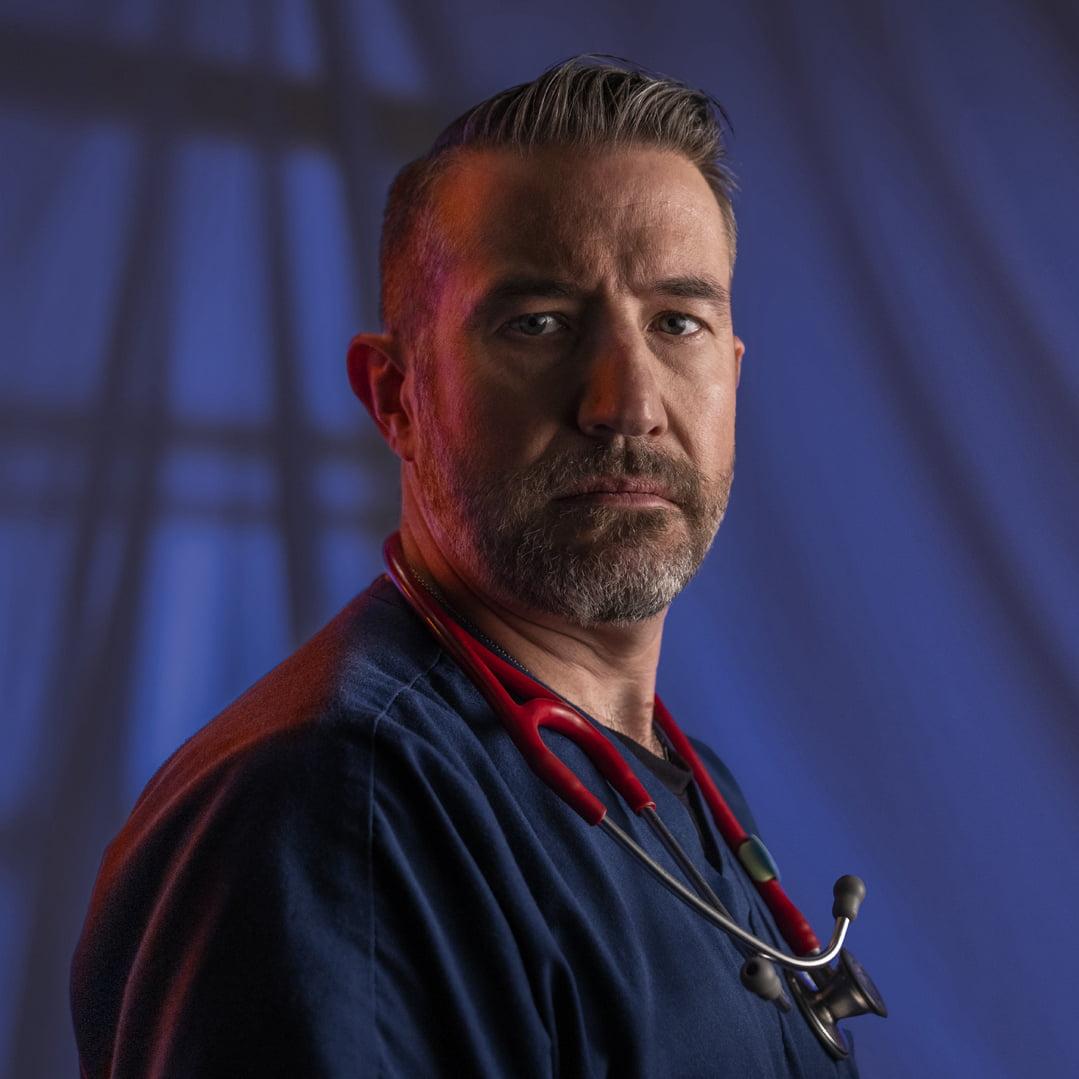

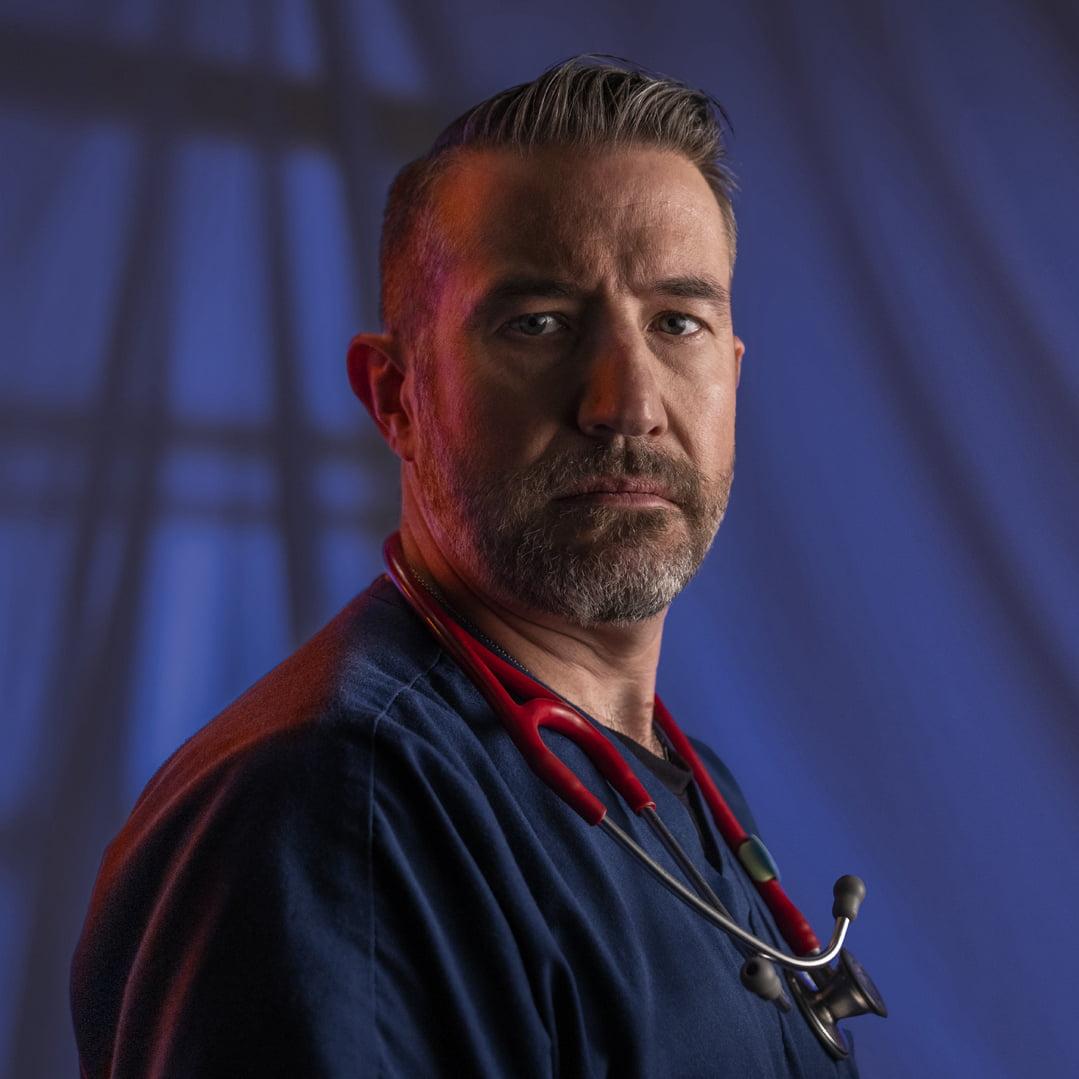

DR. KLIE | Family & Addiction Medicine Physician

“When you decide to open your arms to someone struggling with a substance use disorder, you’ve already made the most critical step, even if they’re not ready to seek treatment.”

During my residency as a doctor, I loved spending time with expecting mothers, and at the same time, I became increasingly concerned about the opioid epidemic. This had me ask, “How did we get here?” and led me to my specialty of caring for pregnant women and mothers struggling with substance use disorder, who are in a really tough position. First, they need both prenatal care and treatment for a substance use disorder. Second, these individuals face a lot of stigma from society for experiencing a substance use disorder and pregnancy simultaneously.

There are a lot of misconceptions about pregnancy and substance use disorder. The first is “if a pregnant person loved the child, they would stop using” – but the ability to stop and care are completely different. Another misconception is “people who use substances can’t parent safely” – it’s possible for parents who use substances to parent responsibly and lovingly. Lastly, people assume someone who is pregnant needs to detox right away. In actuality, this can be very dangerous. Instead, we need to provide harm-reducing options that keep both mother and child safe.

Expecting mothers ask, “Is my baby going to be taken from me?” or “Did I hurt my baby?” These questions demonstrate mothers’ love, care and desire to parent. For me, these questions reinforce the fact that a substance use disorder does not make you a bad parent.

I’m in a fortunate position where I can offer mothers hope in a few ways. First, it’s not a guarantee that a substance use disorder will have long-term effects on a child. I can also offer treatment programs, resources and encouragement to people at a really important cross-road in their lives. And in return, they give me hope through their success stories and by witnessing their act as loving parents.

When you decide to open your arms to someone struggling with a substance use disorder, you’ve already made the most critical step, even if they’re not ready to seek treatment. You’ve left the door open to future dialogue and treatment.

RICH | Denver, CO

“My mom was able to get me into treatment right away, and her support made all the difference.”

Using drugs was my attempt to cover up a lot of the anxiety, depression and anger issues I had. Within six months of first trying heroin, I was using it daily, which was expensive. I eventually got arrested for stealing electronics from a neighbor to pay for heroin, and went to jail for six months. When I got out I stopped using heroin, started community college, and even made the Dean’s List. I was doing well, so I thought I could drink and smoke weed, but I ended up in the cycle of opioid addiction again – pills at first, then back to heroin. I wanted to stop, but didn’t know how.

I was close to being homeless, and I remember taking a train and hearing a couple talk about addiction treatment. It was like, ‘Why didn’t I think of this already?’ I reached out to my mom and told her I needed help, because I needed someone to tell me it was OK to ask for help, to leave the small stability I had with my job, and get treatment. I didn’t know if treatment would be available to me, but my mom was really supportive of my recovery. My mom was able to get me into treatment right away, and her support made all the difference. I’ve been in long-term recovery since, and mom’s still there for me, literally every day. She sends me a smiley face at the same time every day. And knowing that I have support can make all the difference.

NATHAN | Greeley, CO

“Opioids helped cover for the PTSD symptoms, depression and anxiety that I have.”

A doctor prescribed opioids for a foot injury I’d sustained when I was homeless, mainly to help with the pain. I’d also suffered back and knee injuries when I was in the service. But the attraction that kept me continuing to take them, even past the injury, was in how opioids helped cover for the PTSD symptoms, depression and anxiety that I have. It started off slowly, but then my tolerance and everything increased, so I needed more for them to work. Withdrawals would kick in if I tried to get off them. Eventually, I had no choice but to start buying pills off the street. I tried to conceal what I was doing, but after six months or so, I decided it was time to get treatment. My wife knew what I was going through based on my previous experience with substance abuse, and was very supportive when I started methadone treatments. Because of those treatments, I’m not chasing drugs anymore. I’m very lucky. I’ve been blessed with my support group. My wife, my pastor and my friends–they’ve been understanding and loving through all of it. It’s been very easy to talk about. My mind is much clearer now, and my body is getting healthier all the time. And I’m motivated: just in the last month, I’ve gone back to work as a chef.

KEITH | Denver, CO

“You need to break free of shame and guilt to experience recovery. And recovery helps you break free of shame and guilt.”

I spent many years not being comfortable in my own skin, unable to deal with life on life’s terms. Tragedy and not feeling like myself sent me down a dark path that carried me into addiction. My struggles with addiction started in high school. My mom recognized I had a problem, but I wasn’t ready for help, and she couldn’t find the right resources. When I was 19, I was involved in an alcohol-related car crash that killed my friend and sent me to jail. When I got out, I was full of shame and guilt. I was coping using drugs and alcohol to numb those feelings. My life started to slip away; I lost my wife, kids, and home. From there, my disease continued to spiral out of control. The opioid addiction got worse, and soon I was doing other drugs. By 30, I’d burned so many bridges. I was homeless and selling drugs to fuel my addiction.

Thankfully, I hit a point where I was sick of being sick. I was willing to do whatever it took to change. My probation officer allowed me to go to a free treatment facility, and it was the beginning of a new life. With the help of a twelve-step program, a sponsor, and spirituality, I was able to start peeling back the layers of guilt and shame surrounding the accident, losing my family, and my addiction. I’m so grateful to have broken free from the self-bondage. I wanted to share that freedom with others and change lives. I now work with high school kids who struggle with addiction, and help them recover, one day at a time.

SHERIFF FITZSIMONS | Summit County, CO

“As law enforcement officials, our job is to protect life. Isn’t offering life-saving treatment an extension of that sacred duty?”

I’ve been in law enforcement for over 32 years. In the beginning of my career I spent some time on an undercover narcotics team, and that’s where I first recognized how ineffective our approach was. Arresting and prosecuting people struggling with substance use disorders wasn’t helping those individuals, their families, the communities they lived in or the overall drug epidemic. Today, I serve as the Sheriff of Summit County, where I use what I’ve learned to improve the lives of people with a substance use disorder rather than punish them.

Rather than criminalizing addiction, we need a multi-pronged approach. We still need to address the flow of illegal substances into communities. But we also need to practice harm reduction by offering medication, counseling and naloxone.

As an elected official, I’ve introduced some programs I believe have made a big difference in my community and in people’s lives. As a county, we’ve given Deputies naloxone, allowing them to save lives in overdose situations. We have a program in our jail that provides medications and therapy to treat addiction, giving people a chance to fight their addictions and become whole. We also have a robust co-responder program: an initiative to pair Deputies with mental health professionals for certain calls, bringing safety and mental health expertise to the field. This program has been successful in stabilizing people in the community and getting individuals the help and treatment they need.

If you are a law enforcement leader, getting community buy-in for these programs is essential. Working with community leaders and experts in the treatment, mental and public health fields will make your programs more effective and inclusive.

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to treatment. Just like we have established in mental health, there should be no wrong door for people struggling with substance use disorders to get what they need. Having a range of options betters your chances of getting people the help they need.

As law enforcement officials, our job is to protect life. Isn’t offering life-saving treatment an extension of that sacred duty?

KAYLAN | Brighton, CO

“I let him know that he had my love and support when he was ready to get treatment.”

My husband, Timothy, was a paratrooper in Iraq, and he was overprescribed opioids by his Army doctors after knee surgery. The opioids helped with the physical pain, but he continued taking the pills because they also numbed his emotional pain. It got so bad that he needed to take them just to get out of bed.

For so long I was only focused on helping him in his opioid addiction, but at some point, I realized that I needed to prioritize taking care of myself and our daughter. So, I took her and moved in with my parents, but I let him know that he had my love and support when he was ready to get treatment.

One day he called me, out of opioids and in terrible pain from withdrawal, and told me he was considering suicide. I got him admitted to the VA hospital, and he was put on a treatment plan that combined Suboxone with outpatient therapy. During his recovery, we both joined support groups at our church, where we have a shame-free support system and now know that we are not alone.

ANGELA & ANDREA | Sterling, CO & Eaton, CO

“You can always find professional resources if you don’t have anybody you can reach out to.”

Andrea works in the food industry, and her step-mother, Angela, works at a counseling center, connecting those struggling with people who are familiar with the recovery process. Both are in recovery.

Andrea’s substance use began at a time of grief and had been going on for several years. Her substance use made motherhood and custody of her two children difficult. Eventually, Andrea found out she was expecting her third child. The news sparked a desire for change, and she began her journey of recovery. Andrea stopped her substance use and worked long hours all while carrying her child. She explained how amazing it was to receive the support of her parents, her child’s father, and her step-mother, Angela.

When Angela came into Andrea’s life, they formed a strong connection. Even though Angela is 20 years older than Andrea, Angela explained that they could relate on many levels. They would have long conversations, and Angela being in recovery herself provided a base for their communication. Angela considers her openness to be one of the most important things she was able to provide.

Angela sends Andrea supportive gestures like inspirational books around the holidays. Andrea remarks how helpful it is to read some quotes of inspiration when she needs it.

Andrea’s approach to supporting someone in recovery is to remind them that there is a light at the end of the tunnel. Angela added the importance of connection and considers it to be something everyone needs forever.

Angela and Andrea continue to support each other. Andrea advises those struggling to always reach out to someone—having a partner or someone to talk to allows her to feel hope and talk about her emotions. She says you can always find professional resources if you don’t have anybody you can reach out to.

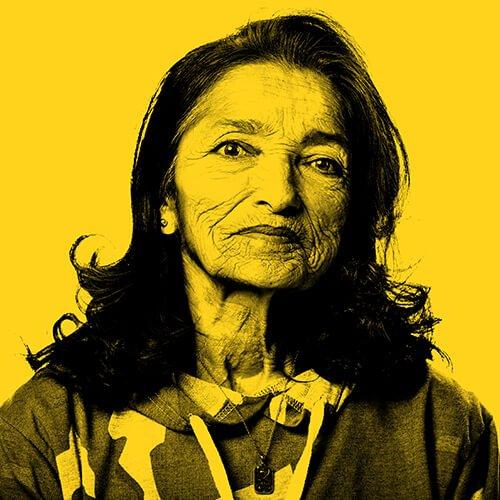

Teresa | Denver, CO

“Now I don’t need anything to get up in the morning, and that’s a good feeling.”

I didn’t start using opioids until I was in my thirties and I started using heroin. The addiction puts you in a bad place. Just having to need it all the time to get going, to do anything–I hated it. Plus, people knowing that I did drugs, the way they’d look at me, the marks on my arm…it was really embarrassing. Other people would tell me, “Ah you could quit anytime you want.” I’d try to tell them it wasn’t that easy, but they just look at you like you’re dirty. Like you’re going to steal everything if they let you in their house. Even if I went to the hospital, I’d get red-tagged because I was an IV user. In time, I just got fed up. The drug didn’t do anything for me anymore; I was just taking it so I wouldn’t go through withdrawals and feel that way. I’d look at people on TV and say, I wanna be like them. So, I got on methadone. I knew if I did it right, I’d finally detox, and they’d help me get off opioids. Now I don’t need anything to get up in the morning, and that’s a good feeling. I’m proud of myself. People don’t realize it’s a disease, and that people need encouragement. That when you’re weak and you fall, that’s when you need someone to lift you up.

Dana | Denver, CO

“I think when people meet me now, they’d never guess some of the things I’ve been through.”

I started using heroin recreationally in high school. It didn’t scare me; it seemed like another white powder that you snort. My family was unaware that I was using until my first overdose. They were shocked, but very supportive and put me through treatment. When that didn’t take, they had me live with them. Nothing they tried seemed to work, and it got to the point where they felt like they were out of options. I left and started living on the streets of Chicago. I did that for two years before getting treatment. I ended up relapsing. Shortly after that, I was driving high on Xanax and heroin, and killed someone in a car accident. I served five years in an Illinois prison.

In jail, there wasn’t much for someone who really wanted recovery. I didn’t want to leave the same person as when I went in, so I took it upon myself to find a way to cope without medication. I used physical fitness, meditation and a 12-step program to shift my focus and surround myself with a positive support system in prison. When I got out, my family saw the change in me. It took a lot of time to rebuild that trust and see that I was serious about it. I think when people meet me now, they’d never guess some of the things I’ve been through. But for those who are struggling, l can share my experience and show how those stigmas can be crushed. I’m a mom, I have a master’s degree, and I’m the director of a non-profit. Those are things that I never thought were possible for me.

Sarah | Denver, CO

“When seeking help, you have to be vulnerable.”

I first experienced addiction after coming out as a lesbian and facing social rejection from my friends. I tried marijuana and immediately knew that drugs would be a way to cope. In and after college, I had a series of knee surgeries that gave me access to opioids. My usage got heavier and heavier until I hit a point where I was spending $3,000 a month on opioids and benzodiazepines online. My combination of drugs gave me blackouts, which is actually what led me to recovery. I was driving in the middle of a blackout, and I rear-ended someone. I’m still grateful no one was hurt. The incident led to my arrest, and more importantly, an ex-girlfriend visiting me and convincing me to seek treatment.

When I went to treatment, I was convinced I didn’t have a problem. I thought if I cleared my system of drugs, I would be fine. After a few weeks in treatment, I realized I did have a problem. In some ways, this was relieving; I understood why my life looked the way it did. More importantly, I knew there was a solution. It took me months of treatment and years of introspection, but I’ve now been in recovery since 2013. Treatment and the recovery community introduced me to so many essential relationships. I found people I could call on and people who would help me. My work helping others struggling with addiction has enhanced my life and given me extra purpose.

Alicia | Grand Junction, CO

“Don’t ever be afraid to reach out. There are so many people out there available to help, you just have to ask.”

I started life out as a goody-two-shoes with two loving parents. But, a troubled relationship with my brother made me feel unworthy and unloved. I tried alcohol and marijuana at just fourteen years old and meth by nineteen. I was in and out of treatment programs four times over the next few years with varying levels of success. At one point, I’d achieved four years free of meth use. During that time, I had a son and eventually got married. Unfortunately, my new husband and I began using heroin. In a short period, my mother passed away, I lost custody of my son and my husband went to jail. This period was the lowest in my life. I considered suicide. It was through those dark thoughts that I knew I was ready for recovery.

I used Suboxone to fight cravings while my probation officer helped me get into a treatment program at Oxford House. The combination of medications for treating addiction and the program at Oxford House opened new doors in my life. My recovery paved the way for me to improve my relationship with my family, and most importantly, I’ve got partial custody of my son. Right now, I’m working toward earning more time with my son, and I have a full-time job at Oxford House as an outreach coordinator, connecting people with addiction to recovery communities.

Victor | Denver, CO

“I got introduced after being drafted to Vietnam. People picked up a lot of bad habits over there.”

I got introduced after being drafted to Vietnam in ’71. People picked up a lot of bad habits over there. Mine was heroin; it helped numb me to what I was doing. I didn’t realize I was addicted until about six months in, when I became sick from withdrawals. When I got back from Vietnam, I tested positive for substance use, and they put me in a psychiatric hospital in Aurora, Colorado. If you used drugs, you were crazy–that’s how they labeled us then. I had to stay there for three months until my discharge came through. I’d hurt my back in the army and still had pain, so a doctor prescribed me opioids. That’s when I started shifting from using heroin to taking opioids. I wasn’t using them as I was supposed to, and it probably took about ten years of abusing them before I found treatment. There were not many drug treatment centers then–places where you could seek therapy, or even get on a methadone program. Eventually I found a center where they were able to get me down to a treatable amount, to where it was like I was taking nothing compared to what I initially was. I was ready to face my addiction from a physical standpoint. From there, I really connected with my church, and with their help and prayers, I was able to finally break my chain of addiction. If you have a problem, seek help. I know what worked for me, it can work for you.

Anna | Denver, CO

“Eventually, I was treated by a school nurse who could tell I was struggling with opioid addiction, and she didn’t judge me.”

I struggled with mental wellness and some traumatic events that escalated my sense of isolation going into high school. I started using OxyContin, but was using heroin soon after – I was 14 and desperate for anything that would make me feel like I was OK. Through high school and into college, I was careful not to get caught or be a part of the drug scene. I kept it to myself and did what I had to do to keep up appearances: I was a master manipulator and still made straight A’s.

Yet inside, I was deeply ashamed of my addiction. I didn’t want help; recovery didn’t seem possible for me. I was keeping my grades up, but I’d hallucinate because of my illness, I’d nod off in class, and I was regularly overdosing. Eventually, I was treated by a school nurse who could tell I was struggling with opioid addiction, and she didn’t judge me. For the first time, I felt like I could talk about what I’d been going through, and I started to believe recovery was attainable.

I didn’t feel like I needed a formal treatment program to get into recovery – my parents thought I could get sober on my own – and it worked for a while. Then I relapsed, and the shame that I felt about relapsing almost killed me. Luckily, I have friends who were patient and made my life joyful, and that helped me stay sober. I realize now that being honest about where you’re at is not failure, and going at it alone doesn’t make it better. Having support for your recovery is so important to finding life on the other side – all of the things I’d ever wanted are possible now.

VICTOR | Peer Recovery Coach Manager

“In peer recovery, everyone is a person first.”

My journey to becoming a peer recovery coach started while I was still in jail. I was enrolled in a few programs, and one of those introduced the peer support program. I knew I wanted to change my circumstances, so I applied to be a peer recovery coach while I was still in jail. The organization I applied to told me to get in touch when I was released. It took a while, but eventually, there were some free training sessions available, and that’s how I got my start. It gave me a chance to make a career for myself in a situation where it can be hard to find opportunity.

Peer recovery coaching was introduced in Colorado around 2015, so when I started it was in its infancy, and that was tough because we didn’t always have the support or recognition we needed. The good news is, I was able to shape the program because it was so new. I had the chance to go from a peer recovery coach to overseeing other coaches and directing grant funding for peers.

There’s so much stigma around substance use disorder and recovery, so our language is critical. In peer recovery, everyone is a person first. Labeling someone by their diagnosis is one of the most dehumanizing things you can do. They’re not an “addict,” or defined by their addiction.

We talk a lot about being an advocate – with a little “a” and big “A.” The little “a” is what you do for your clients: speaking to those struggling, getting them in the door, and helping them advocate for themselves. The big “A” is about advocating for changing the system. That part is about improving the structures in place to help those struggling with substance use disorder and, in my case, advocating for more tools, training, and resources for my fellow peer recovery coaches.

As a peer recovery coach, you have to be a good role model. Your actions have a ripple effect. When you’re a peer recovery coach, you aren’t just helping one person at a time; you’re positively impacting everyone in that person’s life. When the community sees your success and effort to help others, they want to invest, so being a good role model has this snowball effect.

The evidence is out there that peer counseling works, which can have this multiplying effect. Supporting this line of work is one of the best tools we have to help people with substance use disorders.

LARS | Florissant, CO

“We need to end the stigma around addiction; it’s not your fault you’re wired this way.”

My first experience with substances came at an early age when I drank alcohol for the first time in seventh grade. In my early twenties, I had multiple knee surgeries, which came with an opioid prescription. Daily use led to addiction, and things began to spiral. Over the years, I had periods of sobriety. These periods never lasted because I didn’t feel like I was really doing the work. It wasn’t until I was pulled over for an aggravated DUI and possession that I started to turn things around.

From this situation, I found pathways to recovery. One of those pathways was that I received court-ordered rehab. I was also able to do some evaluation of myself as a person and how I wanted to share myself with the world. From there, I was able to put in that work that’s so essential to recovery. Having a supportive partner was hugely helpful. My wife understands that I can’t be with someone who is going to use substances at all. My support system, competitive nature, dedication to working on my sobriety and being myself have given me a new life. Today, I own a natural pet market and dog wash, I spend time volunteering to do outreach, and I focus on my sobriety.

AMANDA | Denver, CO

“It wasn’t until I stopped stigmatizing myself that I was able to start my lasting recovery.”

I began using OxyContin at age 16; it didn’t take long before I was addicted. Eventually, I started using heroin because it was cheaper. I hid it really well up until I had to get treatment. My mom knew I had been dabbling in weed and drinking, but was shocked when my heavy drug use came to surface. After I relapsed, there were months where I convinced everyone I was OK, and then I’d end up in the hospital. My parents tried everything to keep me grounded and control what I was doing. But I’d gotten so good at manipulating, and I would do anything to get that next fix. I think one of the misconceptions was that I was choosing this, and in a lot of ways, I was. But chemically, it got to the point where it was no longer a choice.

I eventually ran out of money and came back home, and it was seeing the pain of withdrawal that really changed how my mom saw addiction. I was violently ill, and my mom was my nurse. At that darkest point, when she was feeling so helpless and not knowing how to help me, she finally understood that it wasn’t a choice to use. From that point, she was ready to do whatever it took to help me recover. Once I had her support, that was when I finally realized that I needed to recover for my own well-being. It wasn’t until I stopped stigmatizing myself that I was able to start my lasting recovery.

ANTOINETTE | Dacono, CO

“One of the most encouraging things for someone struggling with addiction to hear is there are people who care about their recovery and who want to help.”

I wanted to work in treatment after realizing there was a huge need. A lot of people are struggling with addiction, and not enough people are trained in treatment. It’s exciting to see people who want to make a change, especially with the help of medications.

Medications to treat opioid use disorder are exceptionally effective. These medications take care of the body and mind by combating cravings and reducing painful withdrawals. Treatment programs try to find the right medications for you based on your needs, and you are not locked into medication once you choose. Most programs offer other support like counseling, case management, and help finding a job. You will have a support system to help you set and achieve goals. Most treatment can be done through outpatient care, going to a treatment center to get medications regularly, and allowing you to go about your life. The goal with any treatment program you choose is to regain the life you envisioned for yourself.

There’s a misconception that using these medications trade one drug for another. No one should feel shame for needing medication. If you know someone who judges the use of these medications, people in the treatment community can help them understand it.

The cost of treatment may feel overwhelming, but there are more resources available than ever before. Medicaid and Medicare are the most widespread options and may cover 100% of your cost. Applying is easy, and treatment centers will help you with your application. Other payment options could include working with your insurance or providing a sliding scale fee or grant funding to find the most affordable payment option. No one is turned away from treatment because of cost.

MICHELE | Erie, CO

“Because of the stigma associated with medication-assisted treatment, he couldn’t tell them he was using Suboxone, even though it was keeping him off heroin.”

My son Adam’s substance abuse started at a young age, and it eventually escalated from alcohol to heroin. He was arrested for stealing money to buy heroin, and when I bailed him out of jail, he told me about his opioid addiction and that he wanted help. He got on Suboxone and then into a sober living house, which was abstinence-based. Because of the stigma associated with medication-assisted treatment, he couldn’t tell them he was using Suboxone, even though it was keeping him off heroin, otherwise they would’ve kicked him out.

The treatment worked for a while; he was working at the sober living home and helping others into recovery. But once he moved out and tried living sober on his own, he started drinking again. Unfortunately, he’s been caught in a cycle of trying to stay sober – he tried to take his life, was in a coma, got sober, and has relapsed with alcohol and heroin. Relapse is an expected part of recovery, but it’s like he doesn’t feel worthy of a good life, and I think he uses that as an excuse to escape rather than facing his addiction. It’s extremely difficult for me, as a parent. I want to fix him, because I know you can’t do it alone. I stay focused on loving him unconditionally, and instead of being part of the problem by judging him, I continue to support him, and hope he can find lasting recovery.

KALEY | Colorado Springs, CO

“It was the first time they realized that I didn’t choose to be messed up.”